The Guardian: Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920 review – revelations and mystifying omissions

Laura Cumming, Sun 19 May 2024

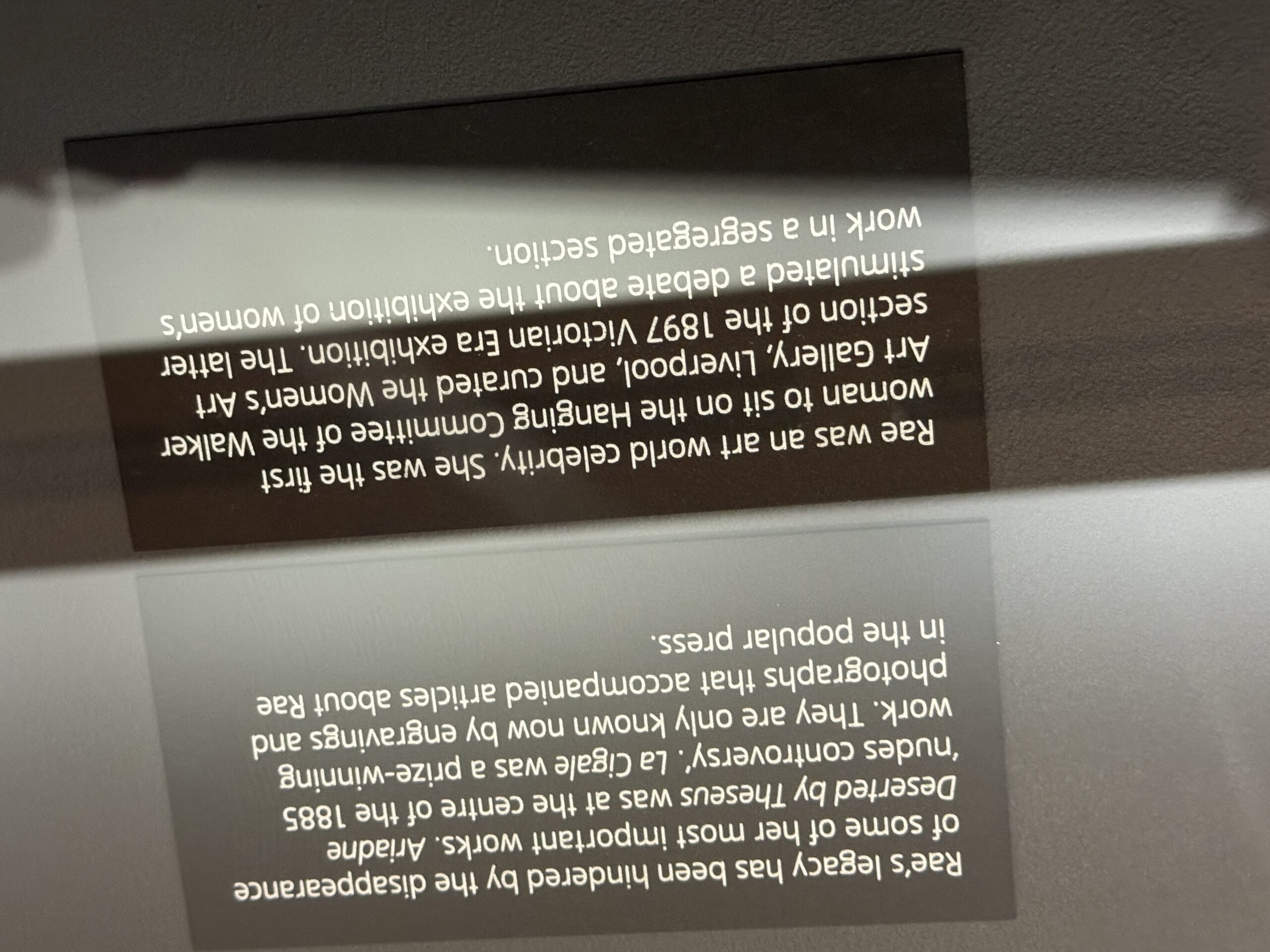

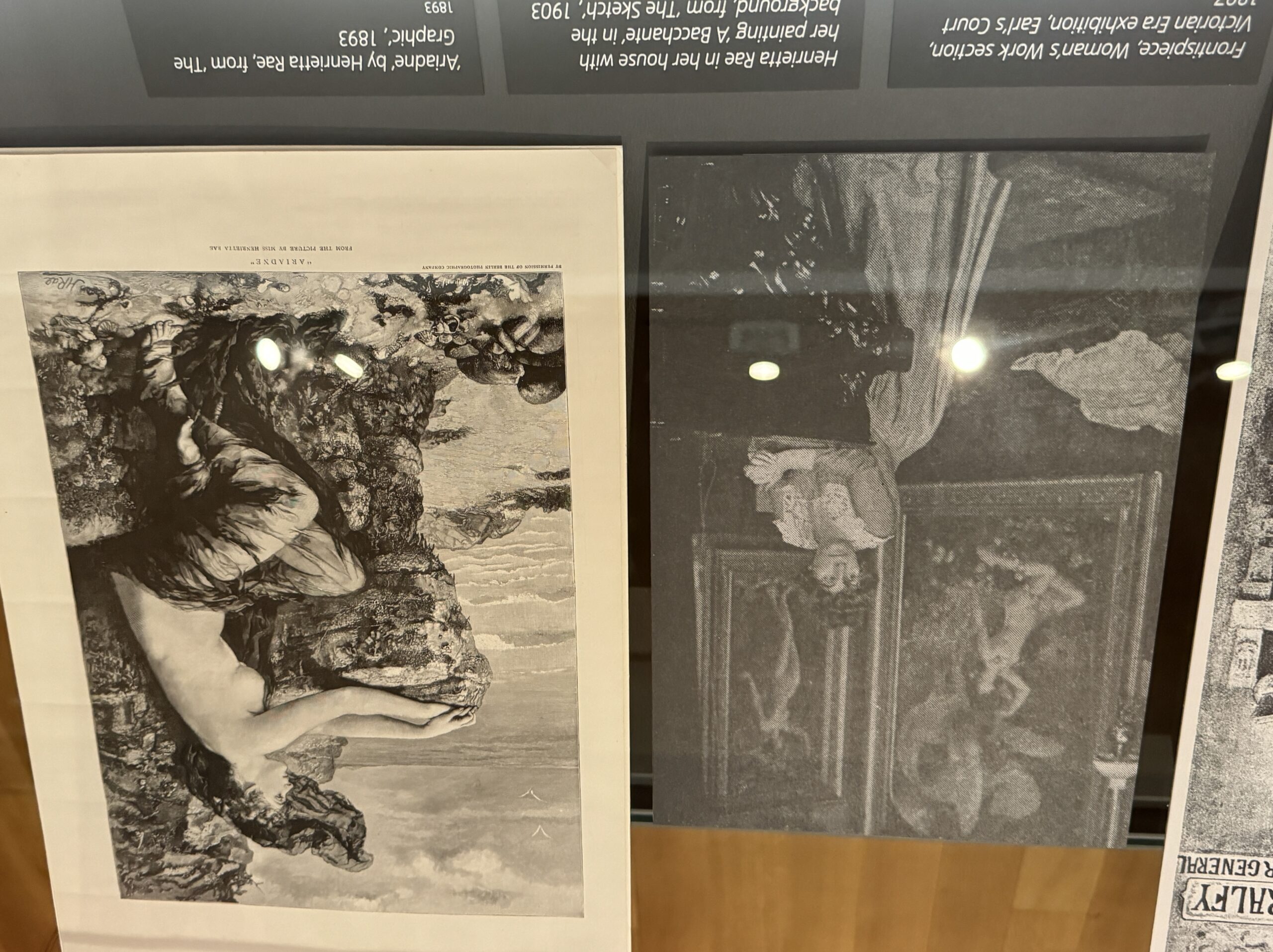

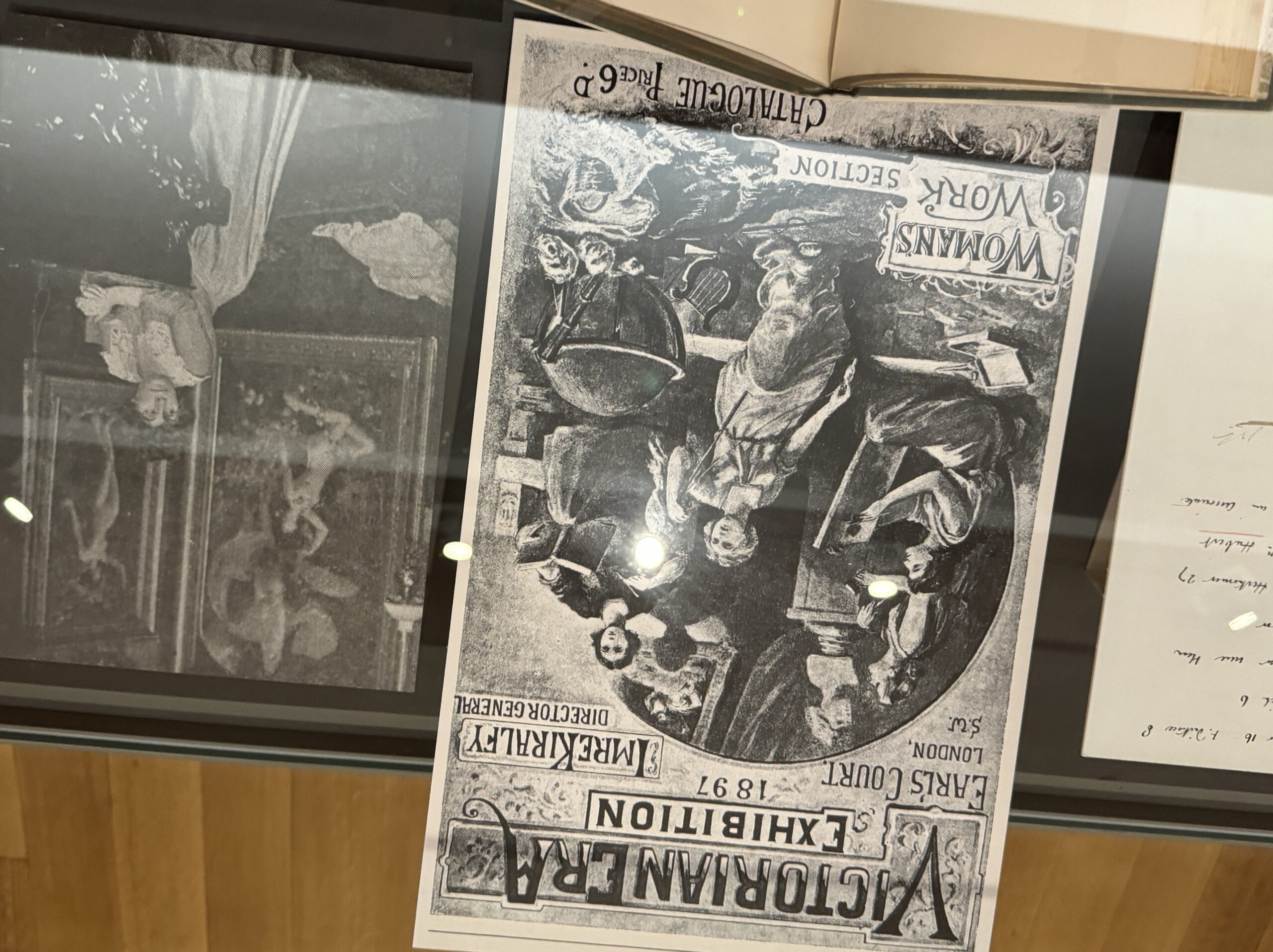

A Flemish ‘paintrix’ at the court of Elizabeth I, a magnificent mouth artist and a glamorous suffragette are finally given their due in a show tracing female artists’ rocky road to recognition. But the story too often takes precedence over the art

Mary Delany (1700-88) was a witty memoirist of 72 when she in effect invented the paper collage in Britain. Noticing the affinity between a geranium and a scrap of red paper, she took her scissors and cut a petal from it freehand. The exquisite plant that grew from Delany’s work looked so exactly like a watercolour people mistook it for a painting. She had discovered a new way, she wrote to her niece, “of imitating flowers”.

Delany’s collages are startlingly beautiful – nearly transparent apparitions materialising on inky black paper. They have the translucence of both watercolour and actual pressed flowers. Two appear in this exhibition: a flowering raspberry glowing crimson against the blackness and a fragile white lily unfurling its petals, as it seems, by night. They might be emblems for the show itself: discoveries, and rediscoveries, brought out of darkness into light.

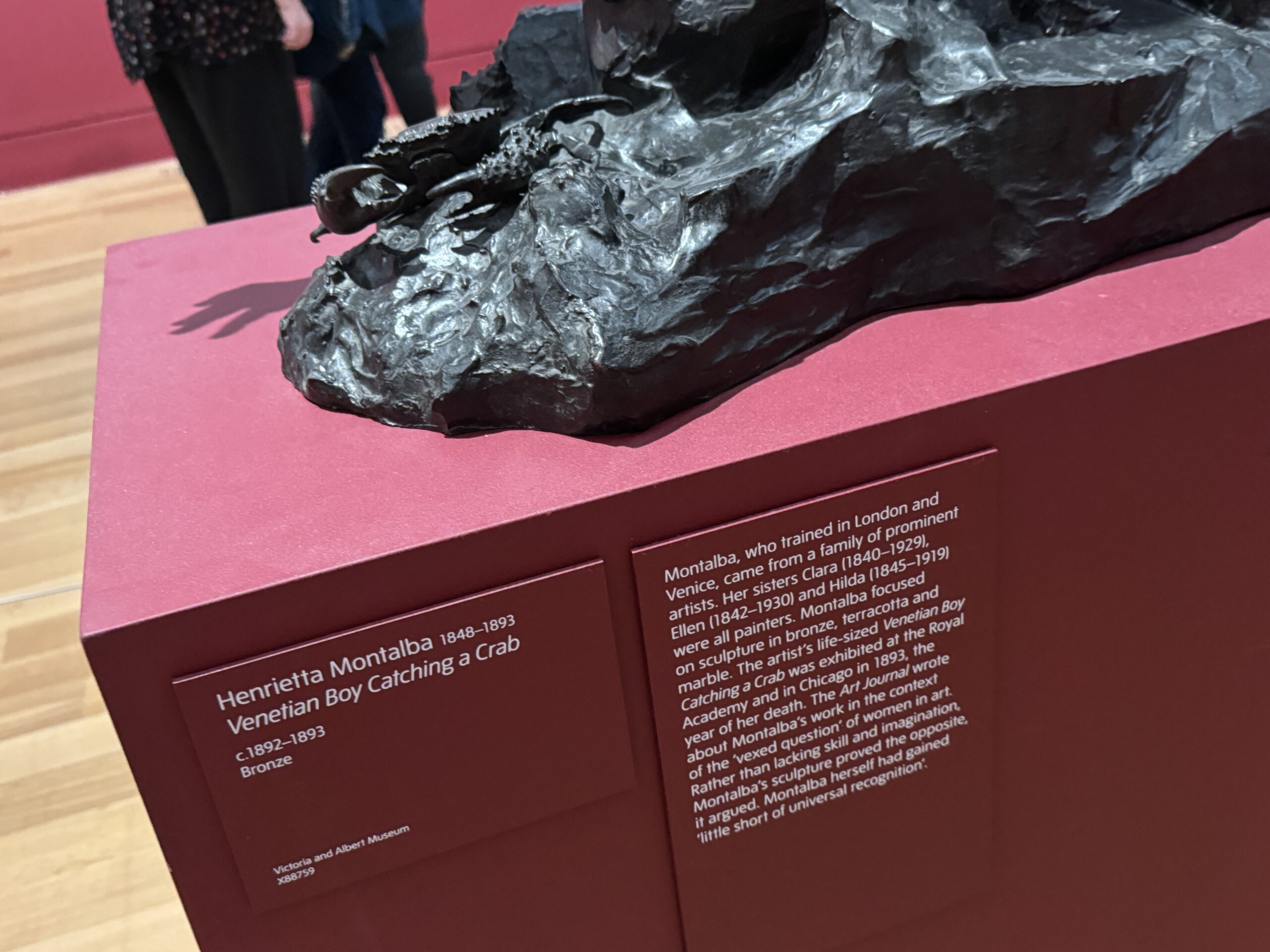

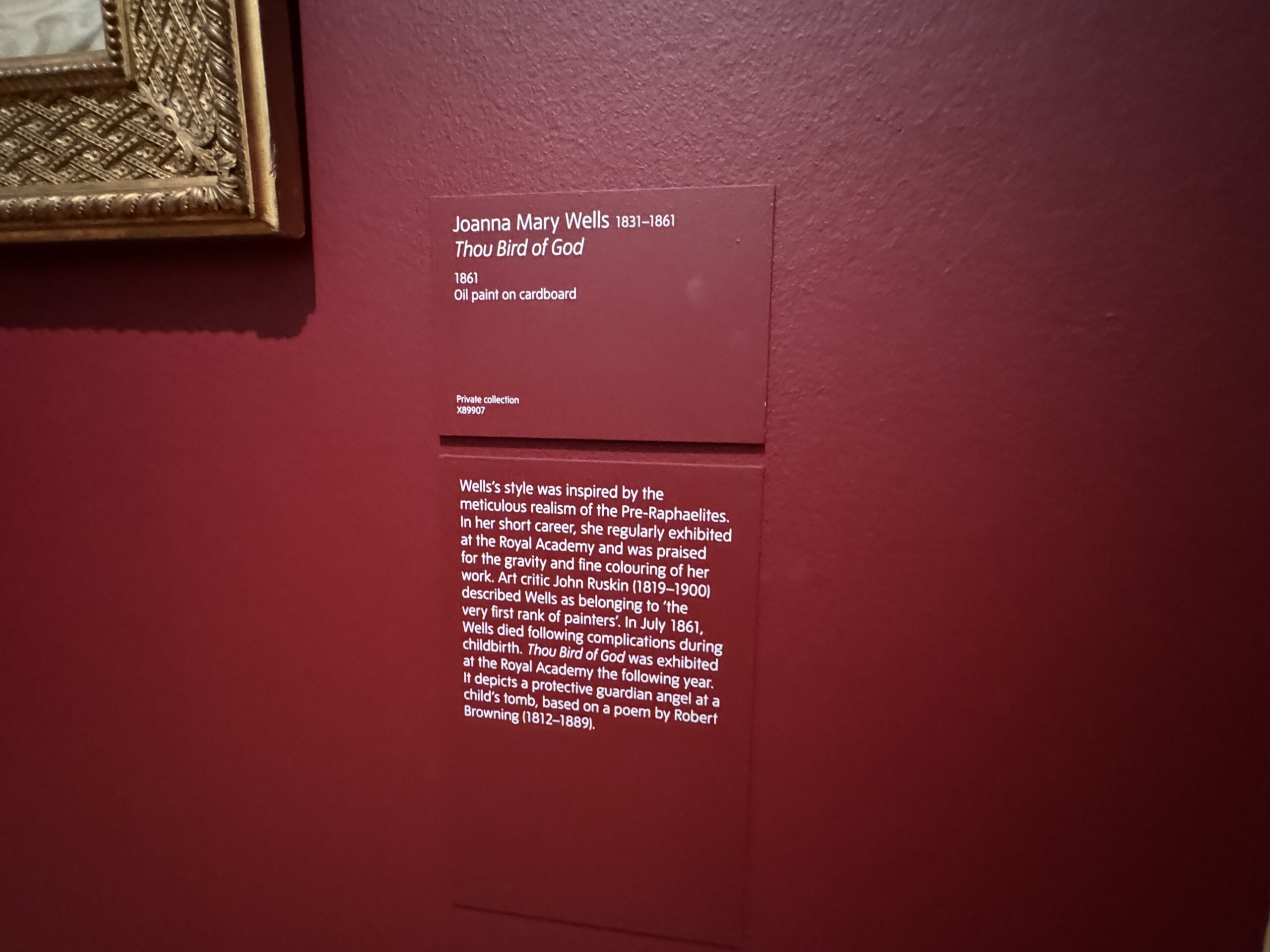

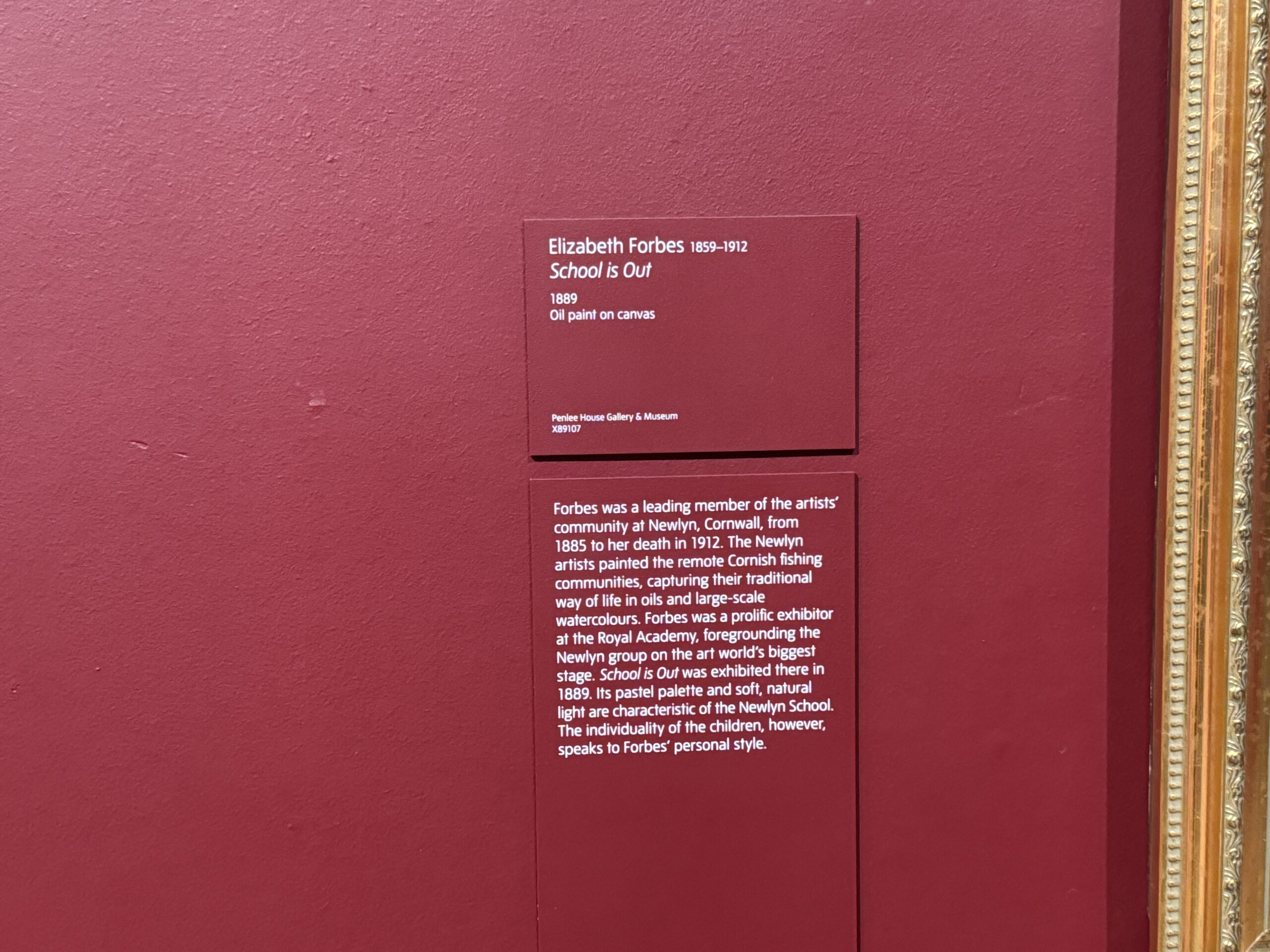

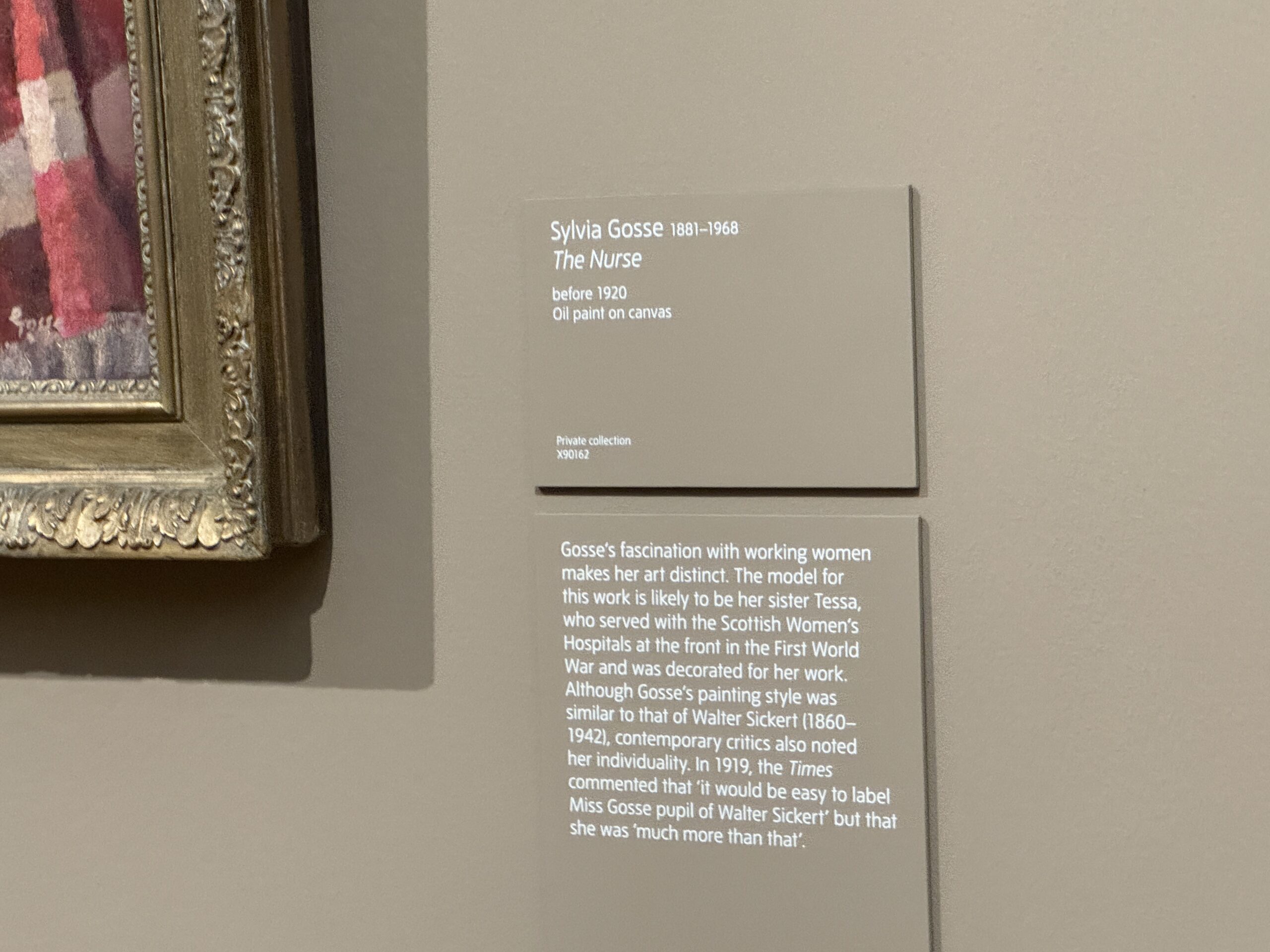

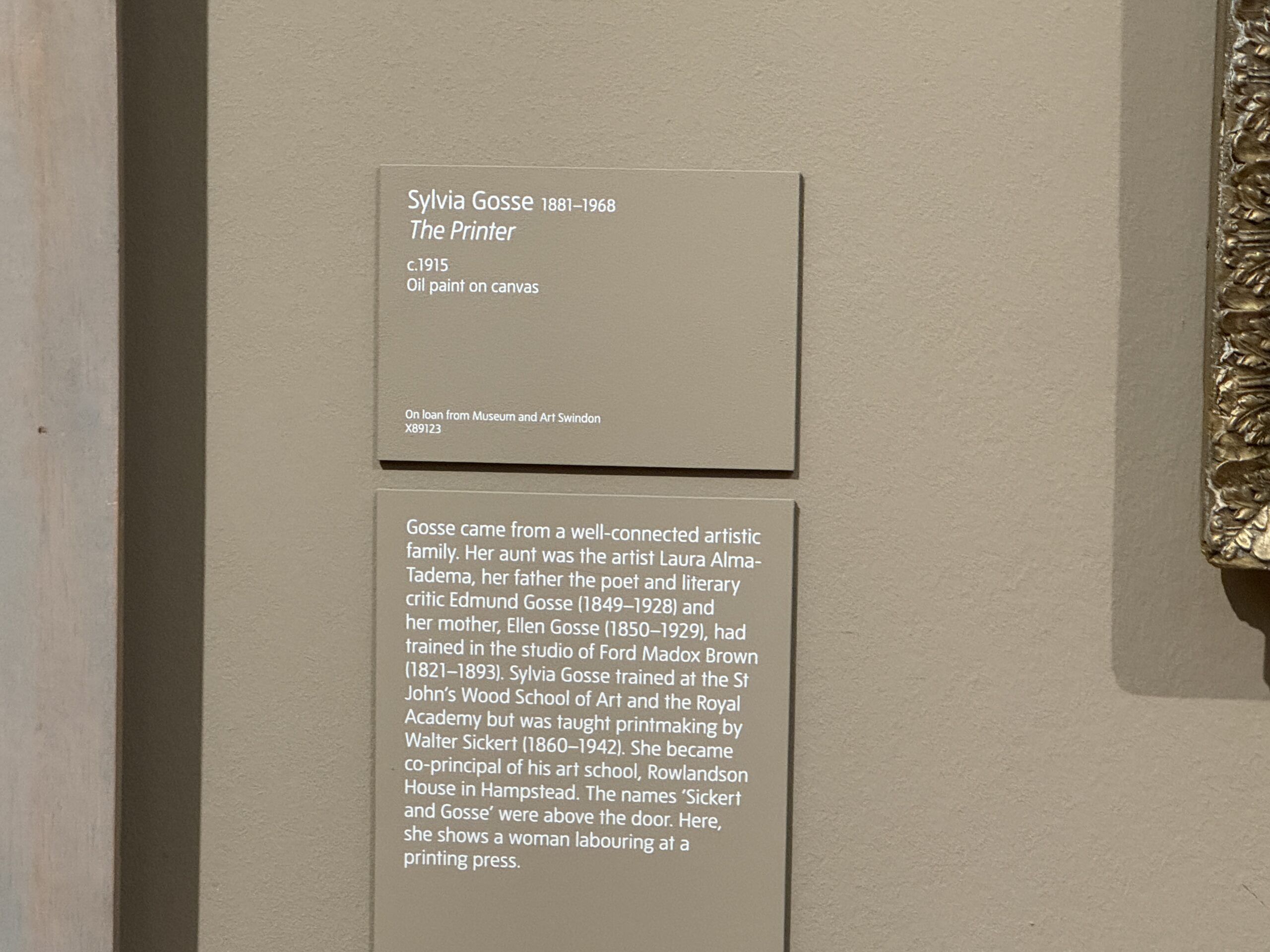

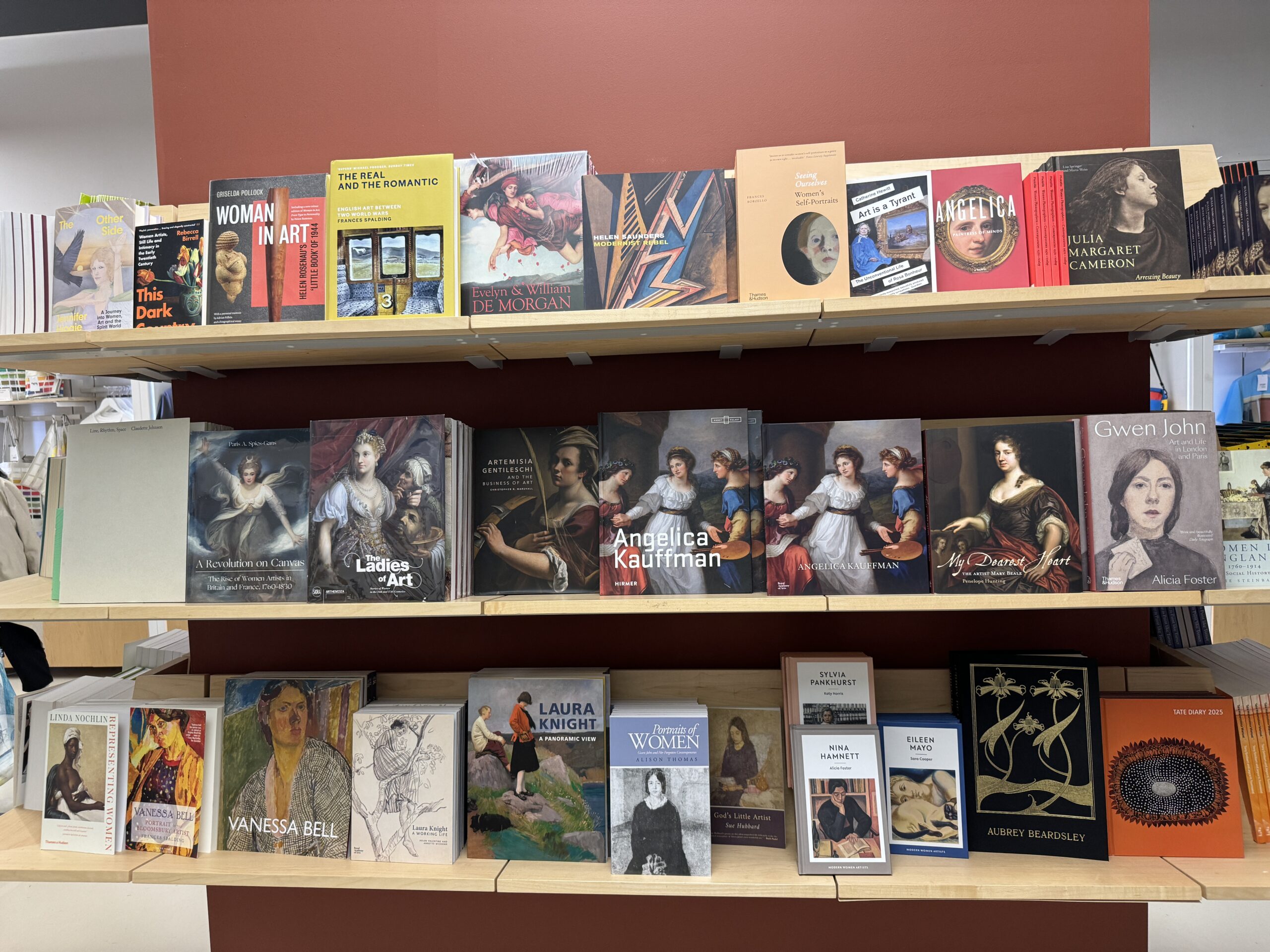

Tate Britain’s Now You See Us spans four centuries of art by more than 100 female artists. It is planted with revelations. Here are miniatures by Levina Teerlinc, Flemish “paintrix” at the court of Elizabeth I, including one of the young Gloriana with telltale ginger eyebrows attributed to Teerlinc. Lively portraits by Joan Carlile (1606-79) show satin-clad aristocrats with watery eyes and occasional double chins, real and recognisable women staring out of the canvas.

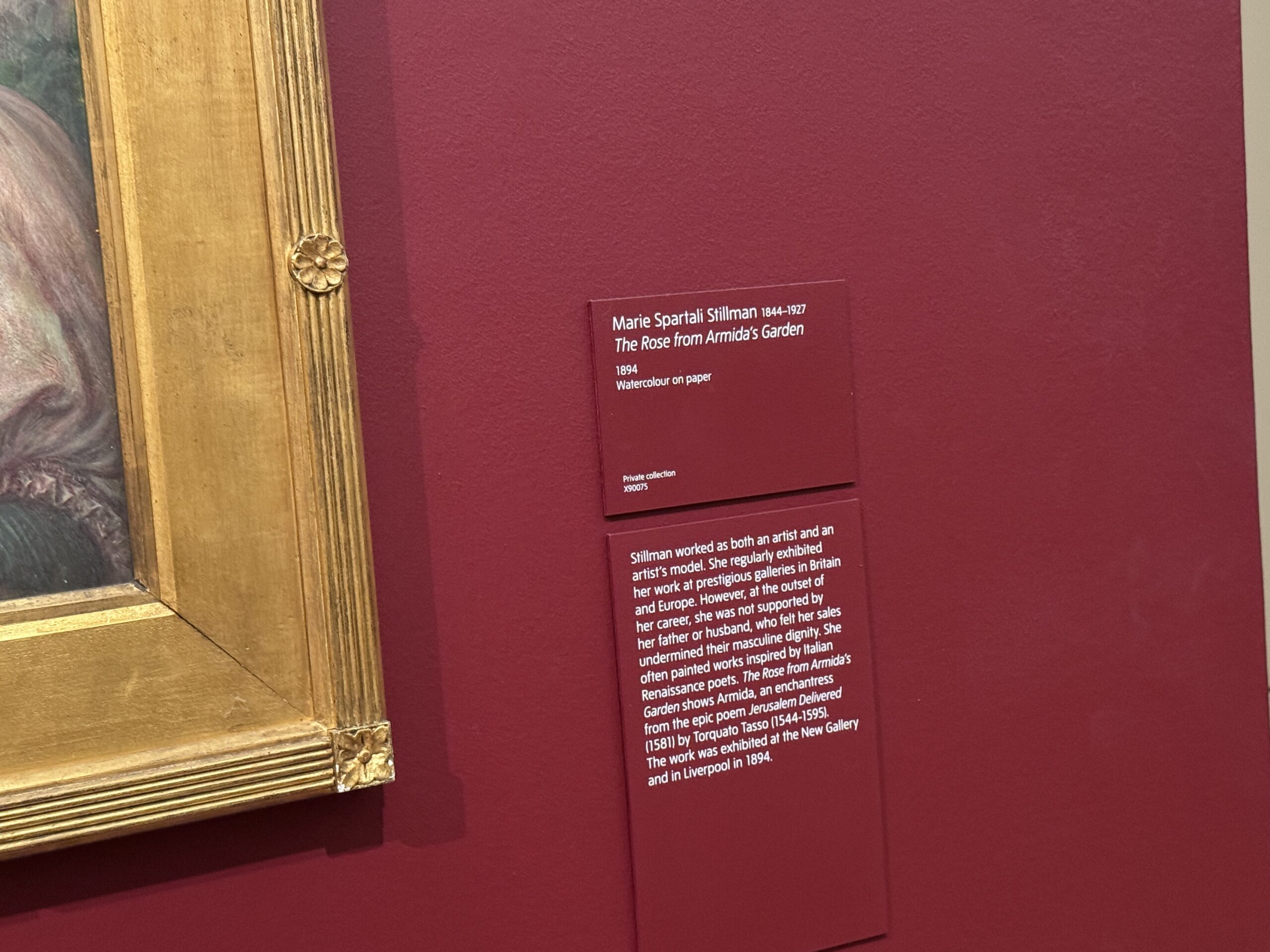

The poet and painter Anne Killigrew (1660-85) depicts herself barefoot, with an expression of unmitigated dismay, pretending to be Venus mourning Adonis. Sarah Biffin’s exceptional self-portrait on ivory (1821), neatly incorporating one of her own crisp miniatures, shows the brush attached to the neckline of her dress. Born without arms, Biffin painted with her mouth.

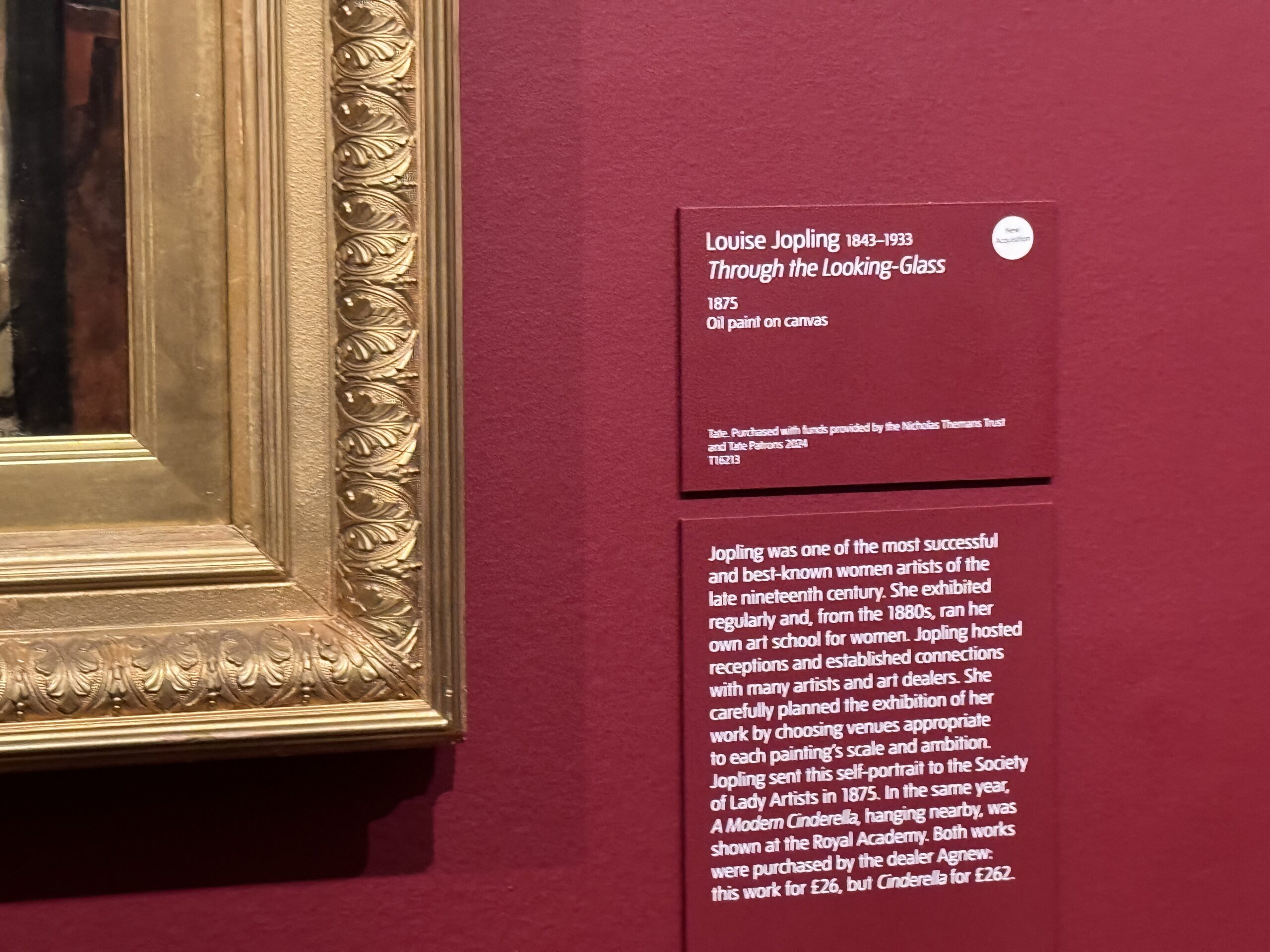

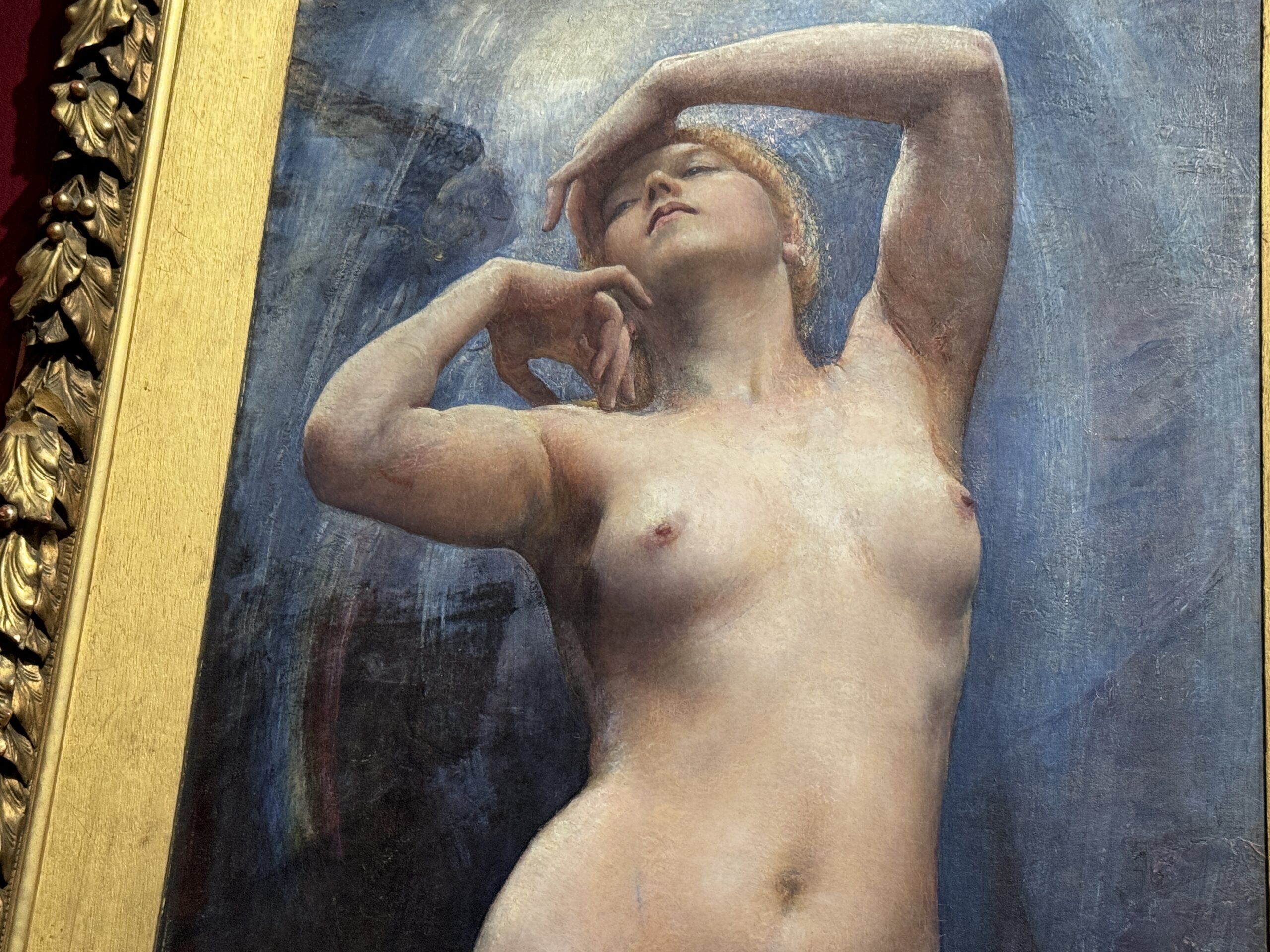

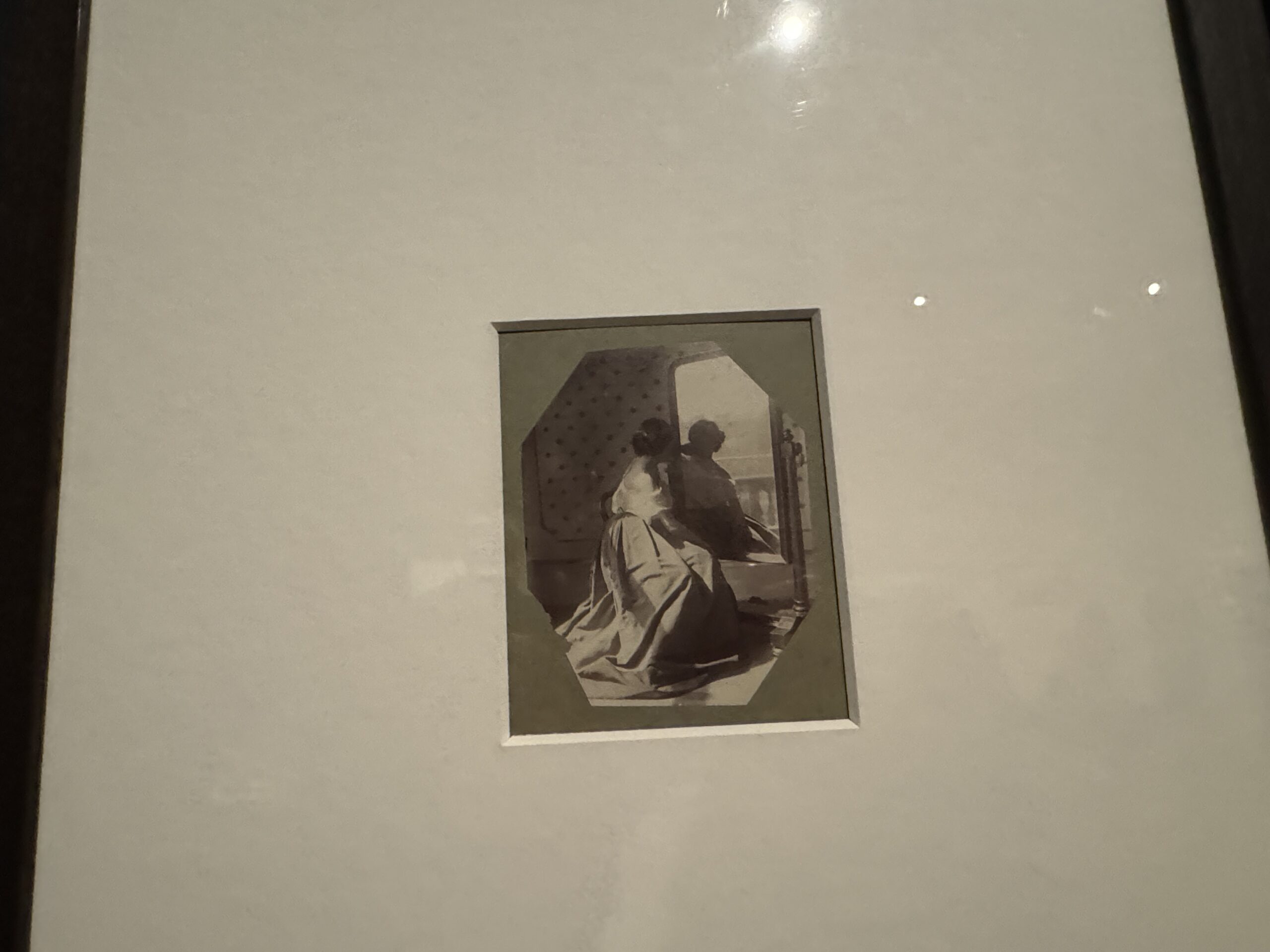

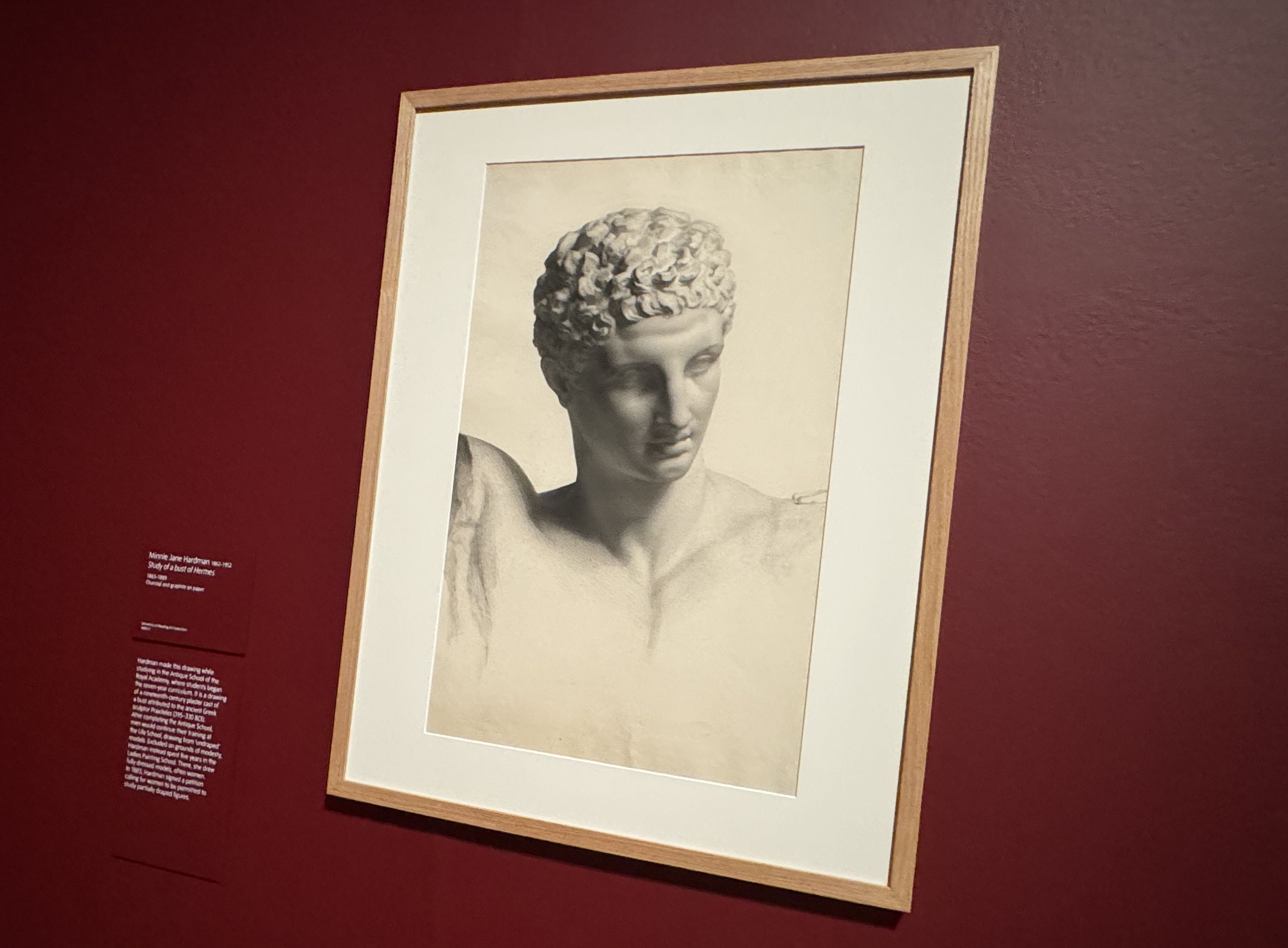

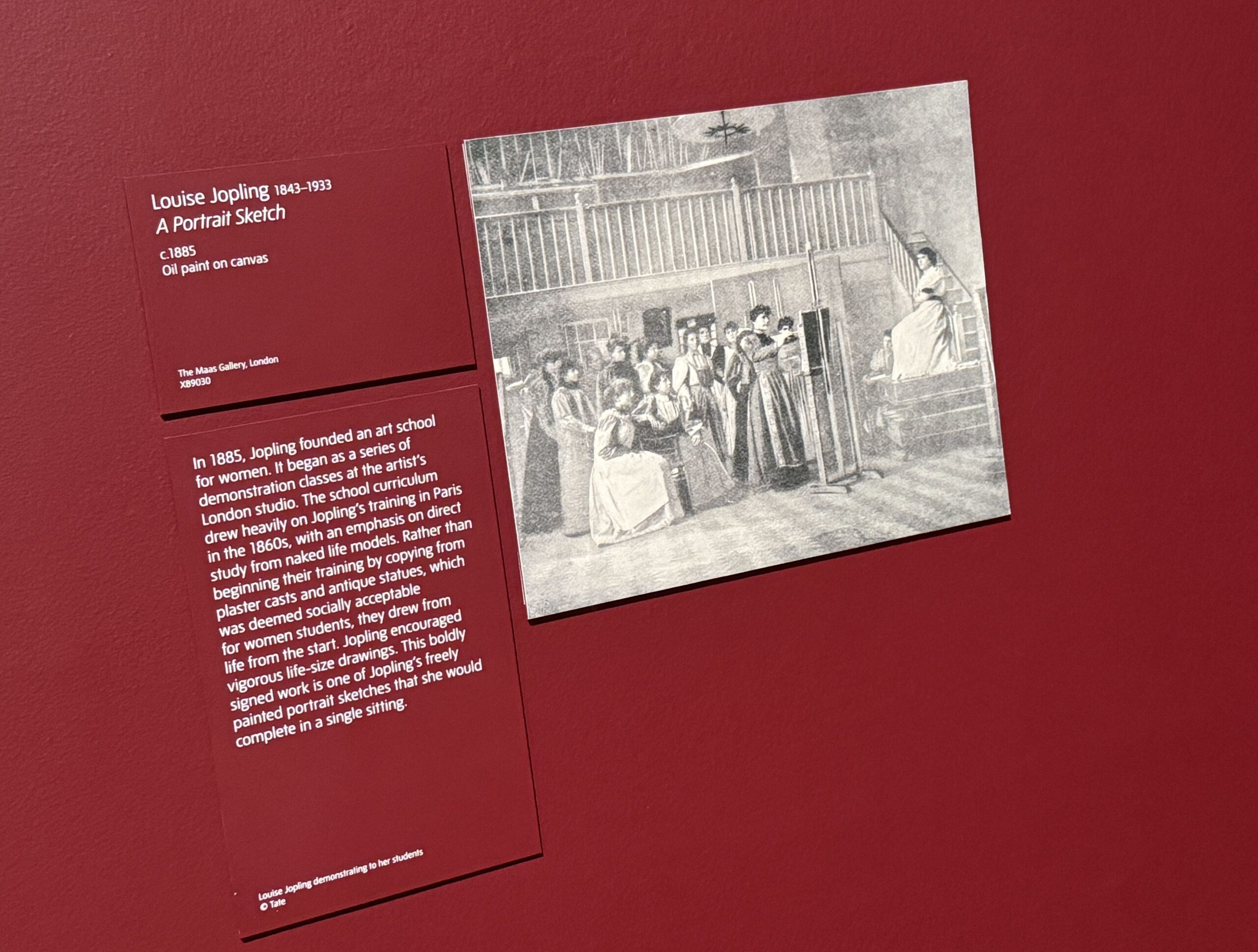

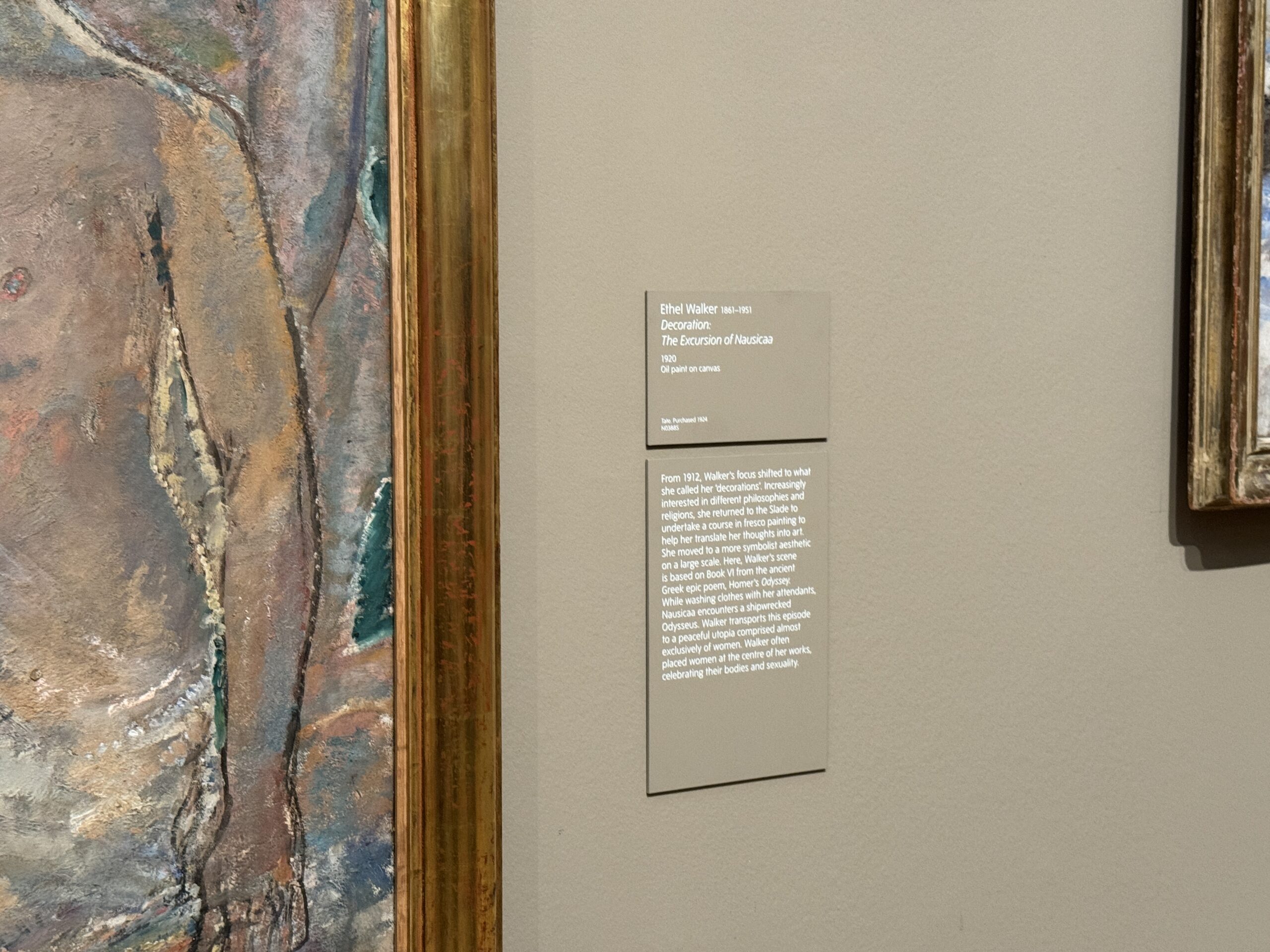

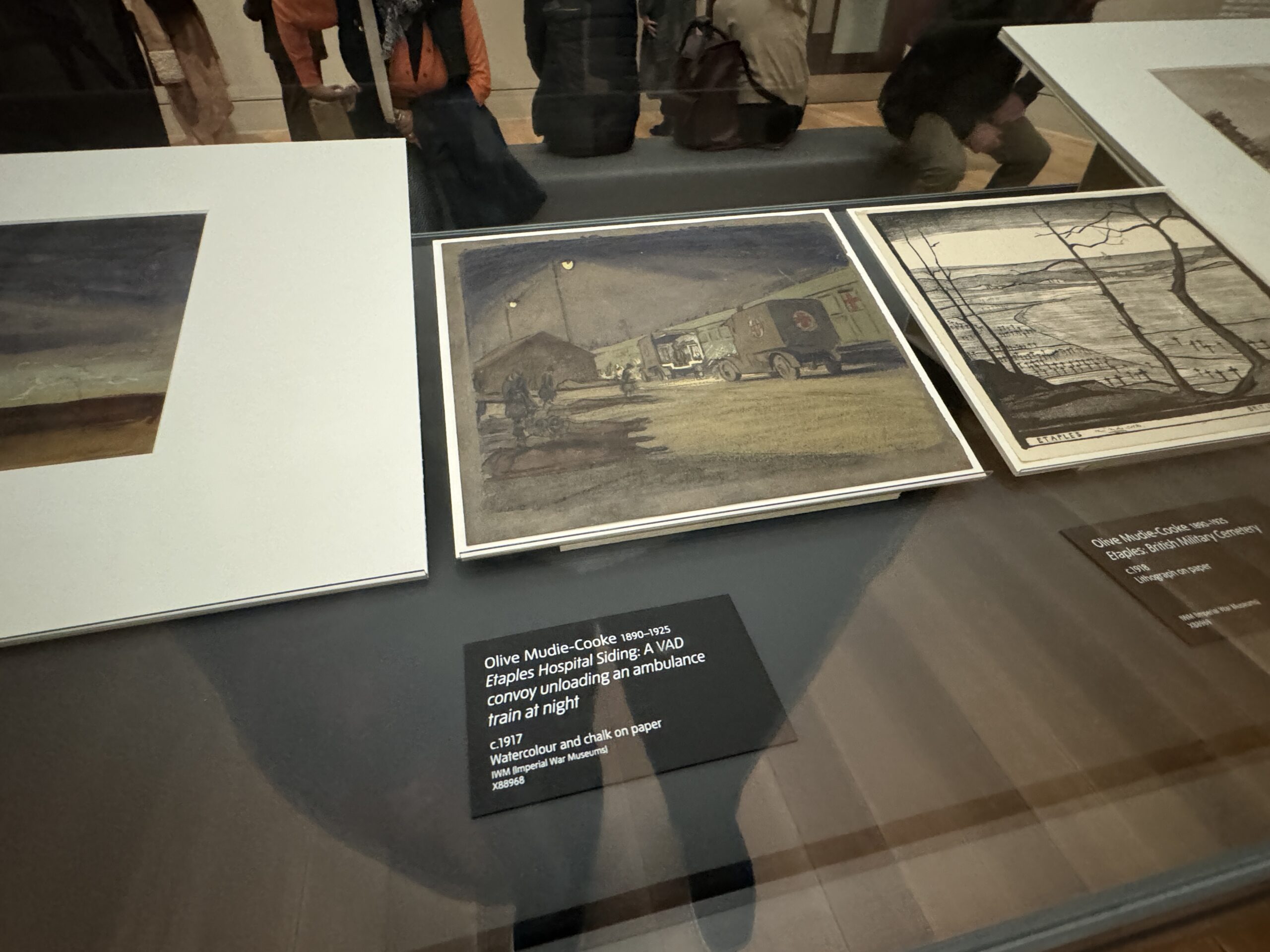

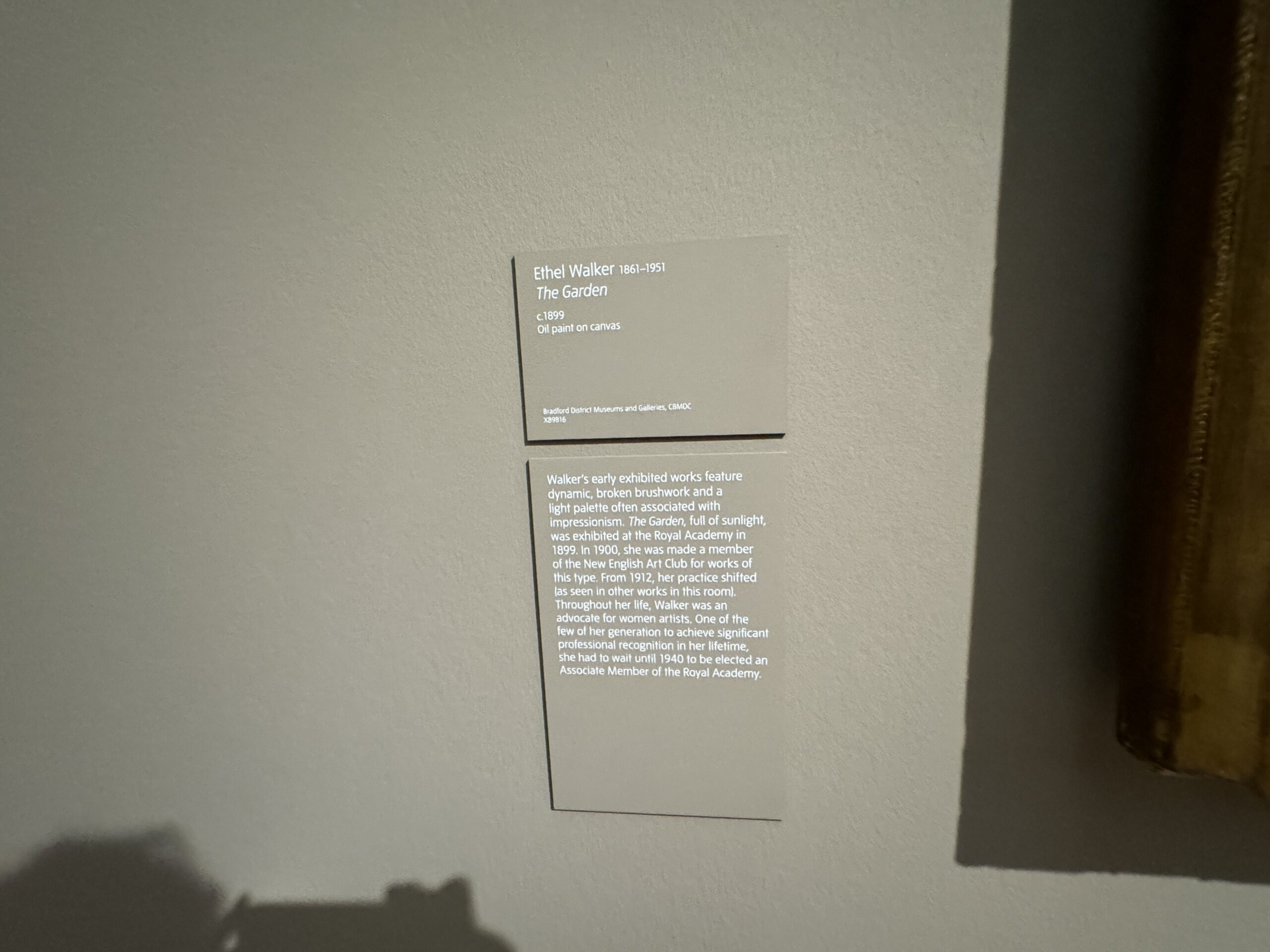

For every celebrated masterpiece – Artemisia Gentileschi’s momentous c.1638 self-portrait with dirty fingernails and sleeve falling away to expose her strong forearm, embarking on an equally bare canvas – there are at least 10 unfamiliar names. Margaret Meen’s glorious passiflora, spare, exquisite and horizonless as a Japanese watercolour, was painted in 1789. Louise Jopling, who studied in Paris and opened her own art school, introduces brilliant colour and seductive draughtsmanship to glum Victorian portraiture. Ethel Walker’s vast frieze of nude bathers, from 1920, shows traces of Cézanne and Degas but presents each woman as a distinct identity in the hazy blue light. Yet it has been as overlooked as its sister works.

Walker represented Britain more than once at the Venice Biennale, and that goes to the show’s central theme, which is women’s road to recognition as professional artists. Some never break through; others rise only to be forgotten again (Biffin, for instance, despite Charles Dickens’s repeated praise in novels). Others cannot make a proper living.

In 1839, Harriet Gouldsmith published (anonymously) A Voice from a Picture, a book in which one of her own landscapes protests at being badly hung at exhibitions and sold off cheap to pay the rent. Gouldsmith once overheard her art praised at a show only for the enthusiasm to wither on the discovery that she was female.

To this end, Now You See US opens not in 1520 but 1780, with Angelica Kauffman’s saccharine allegory of Invention as a goddess in wafty neoclassical wisps. An awful painting, to be sure, but it qualifies on two grounds: its personification of invention as female, and because Kauffman was one of the two female artists who co-founded the Royal Academy.

Here is a dilemma straight away: which should take precedence, the painting or the fact? Should the show present art on its own terms, or as instance, evidence, expression of social history? It is an extremely complex remit, especially given the high success of Tate Britain’s Women in Revolt: Art and Activism 1970-90, only recently closed and now touring to Edinburgh then Manchester. Now You See Us tries to go all ways.

If Helen Allingham’s twee cottage gardens, then why not the visionary genius of Beatrix Potter?

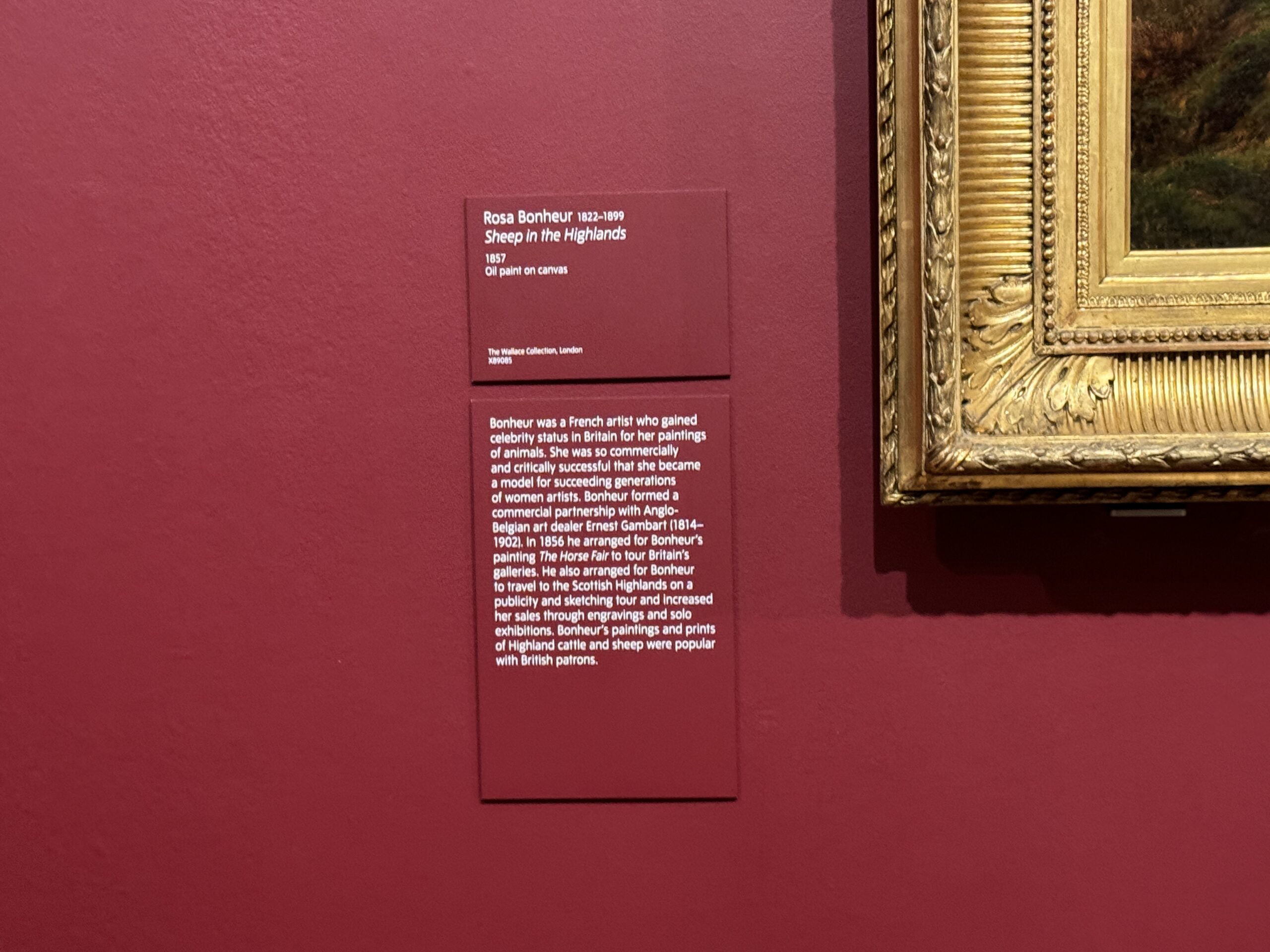

So here is a marvellous 1857 painting of sheep on a Highland peak by French artist Rosa Bonheur, their soft wool graced by the fine Scottish light, their spirit of closeness made beautifully clear. It is a great work on loan from the Wallace Collection. But though Bonheur was extremely popular in Britain, particularly after Queen Victoria’s patronage, she only visited twice for a matter of months.

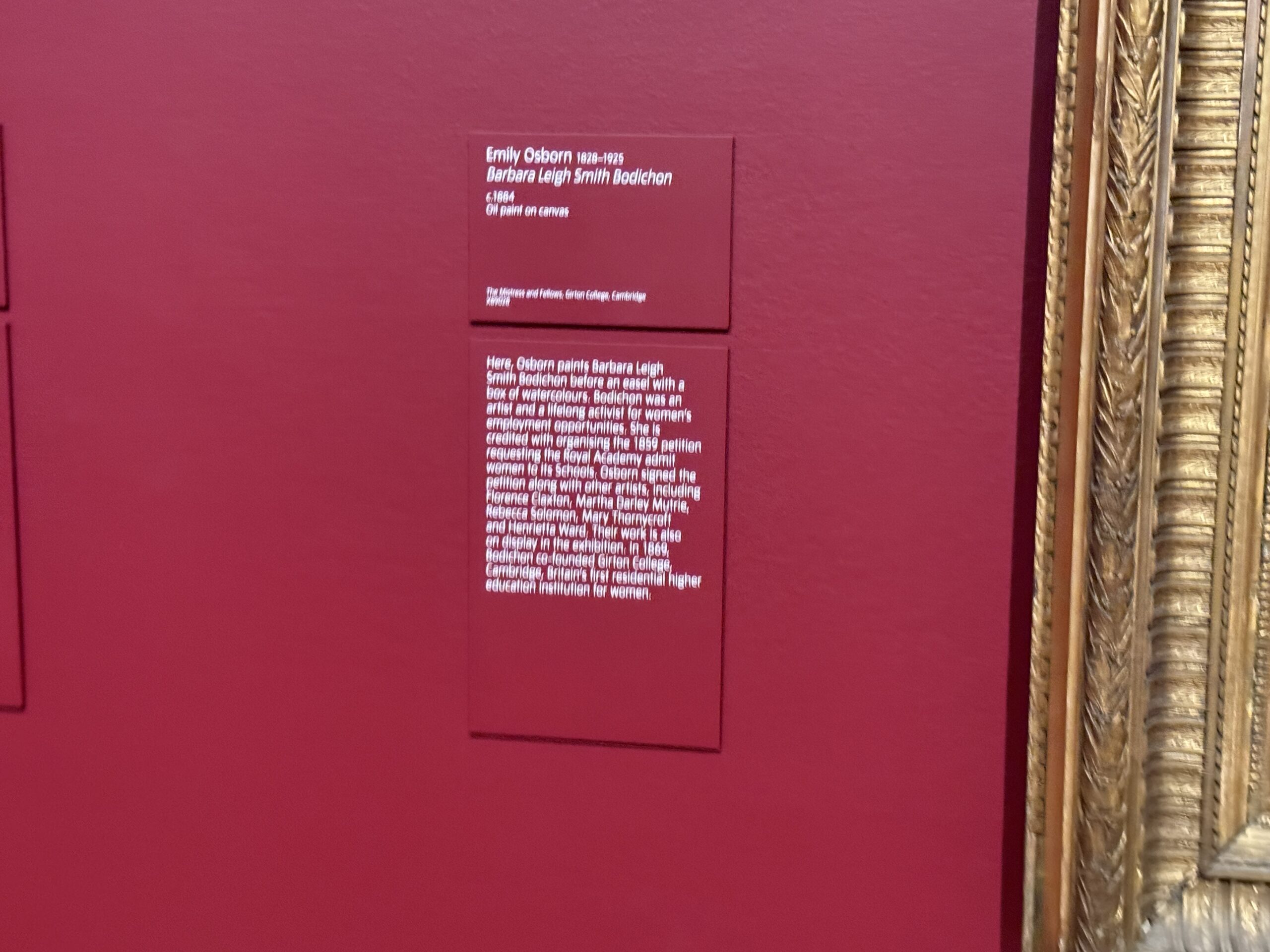

But she has a double function in this show, which is to reappear as an icon of female success in a neighbouring picture by Florence Claxton. Woman’s Work, 1861, is a satire on professional inequality, allegorised as a throng of women walled inside a ruined house, all the doors and windows blocked. Bonheur alone overcomes the barriers, painting the view from high up on a ladder. It is a distinctly literal skit.

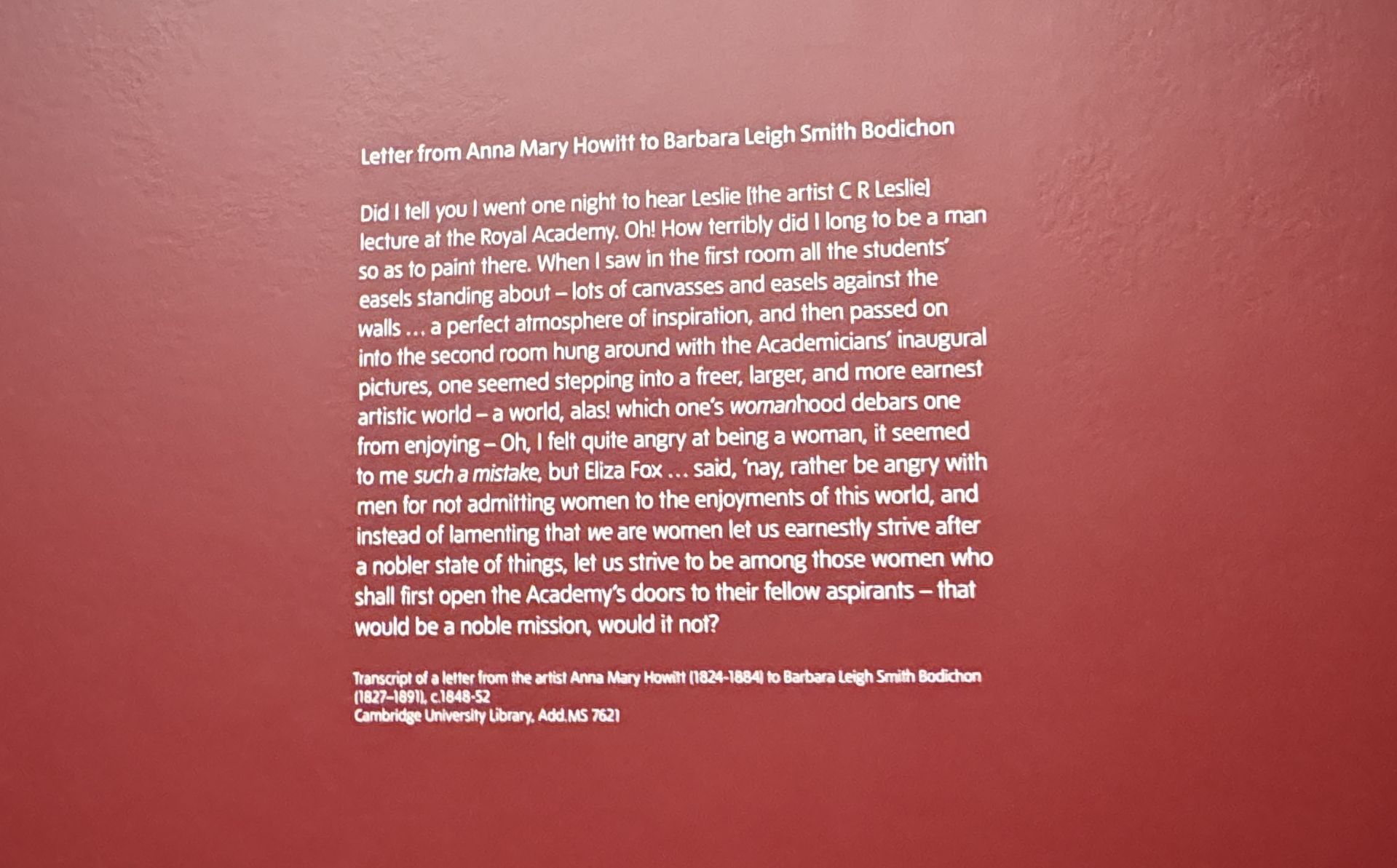

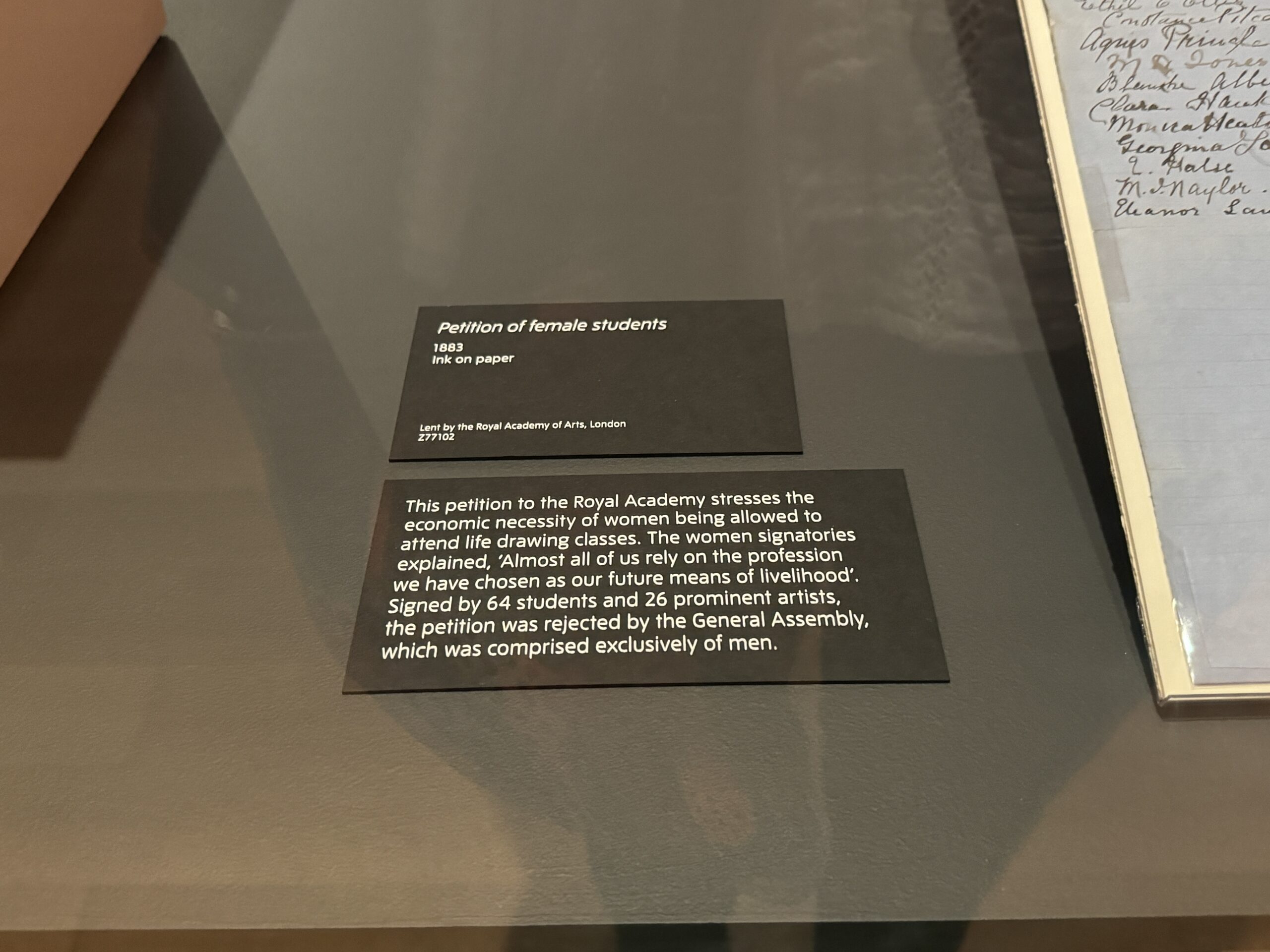

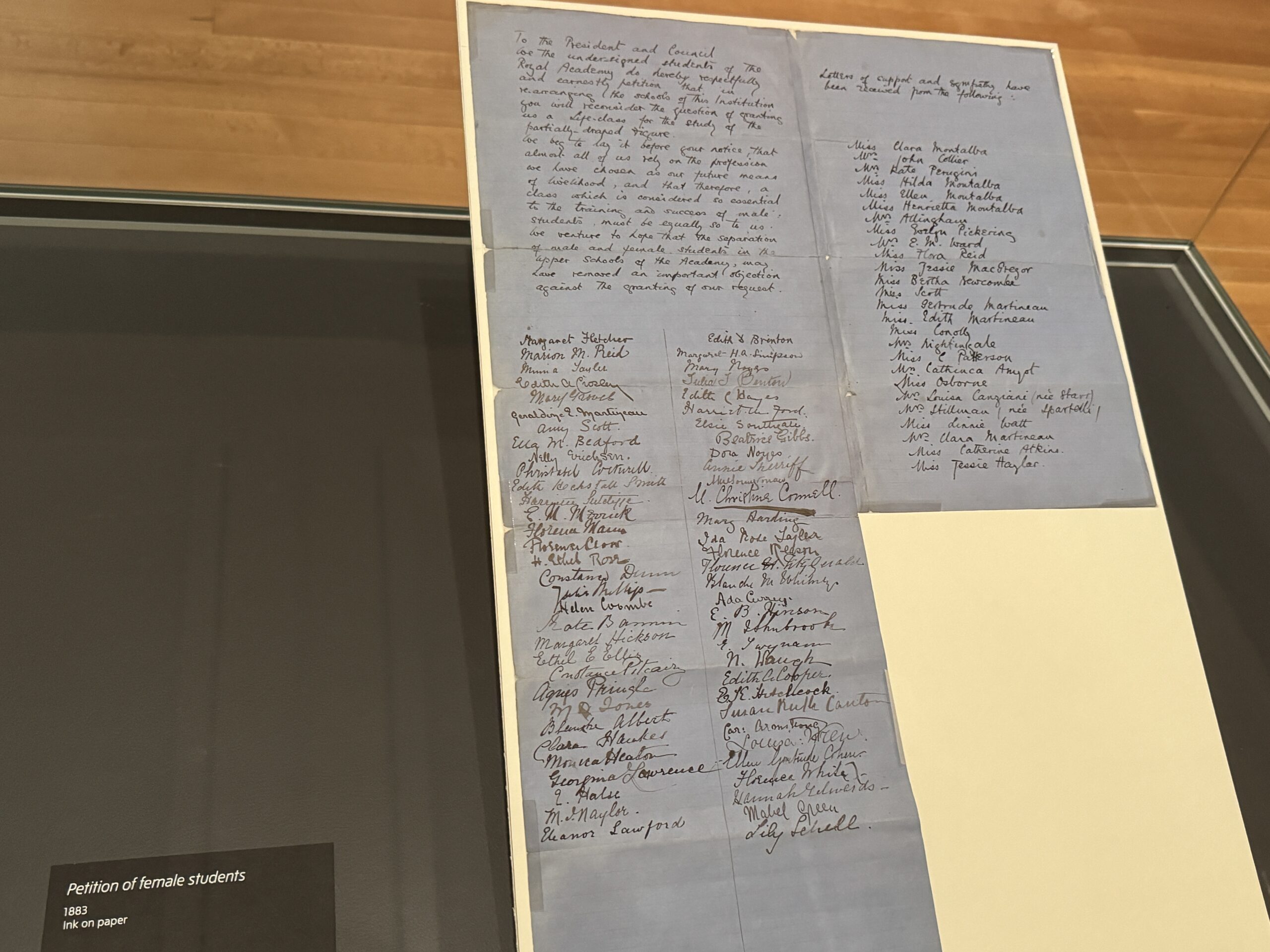

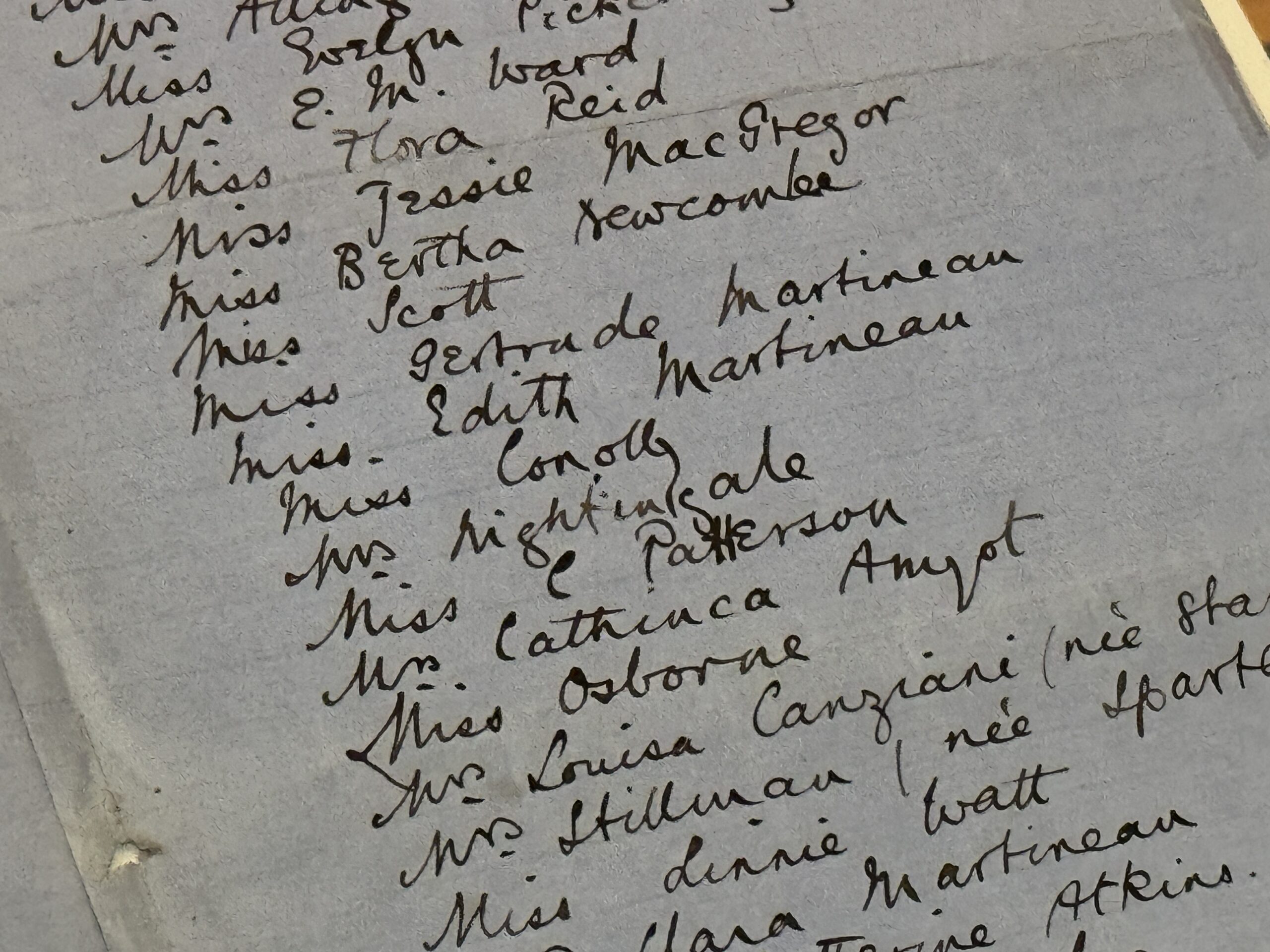

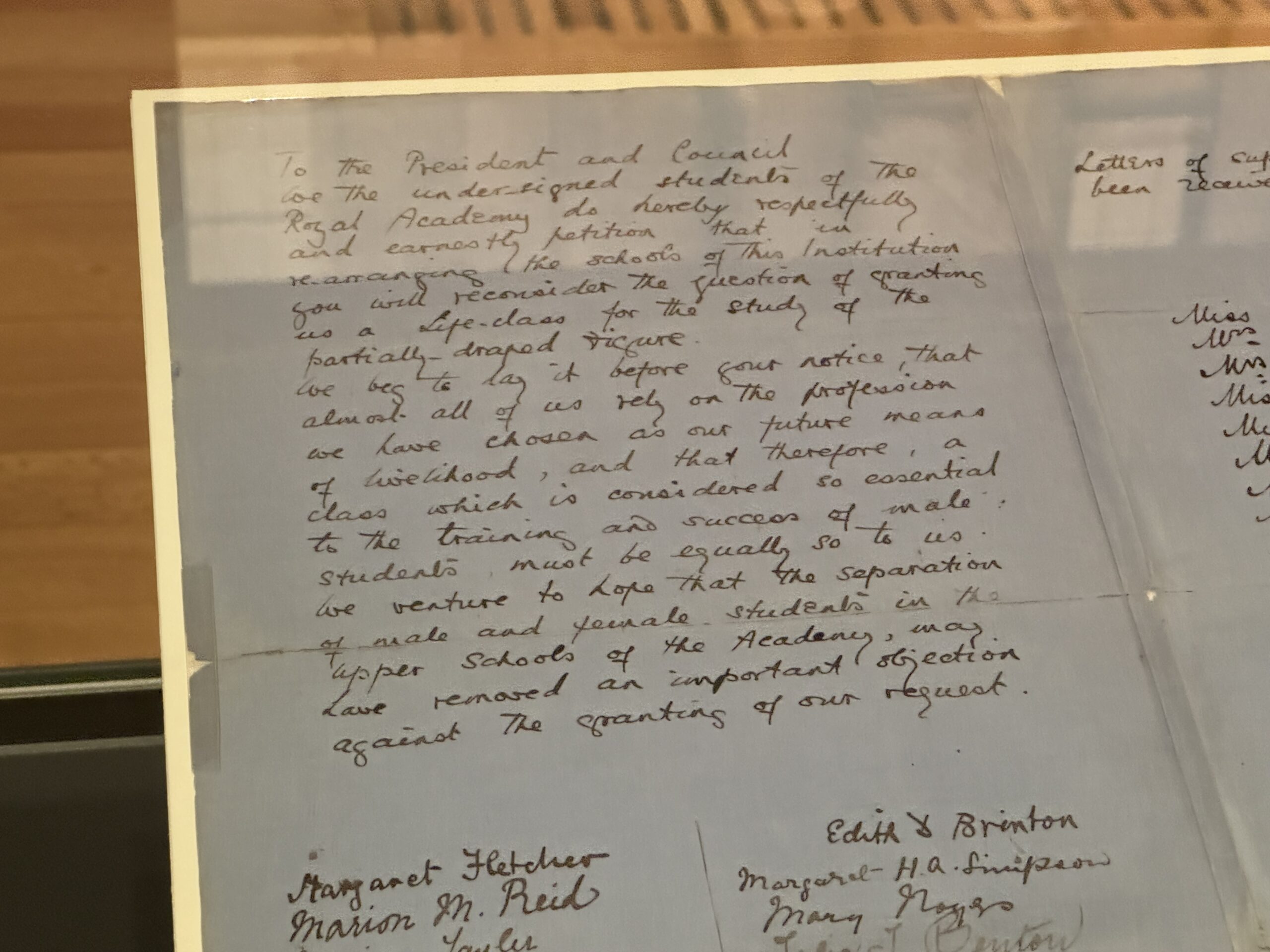

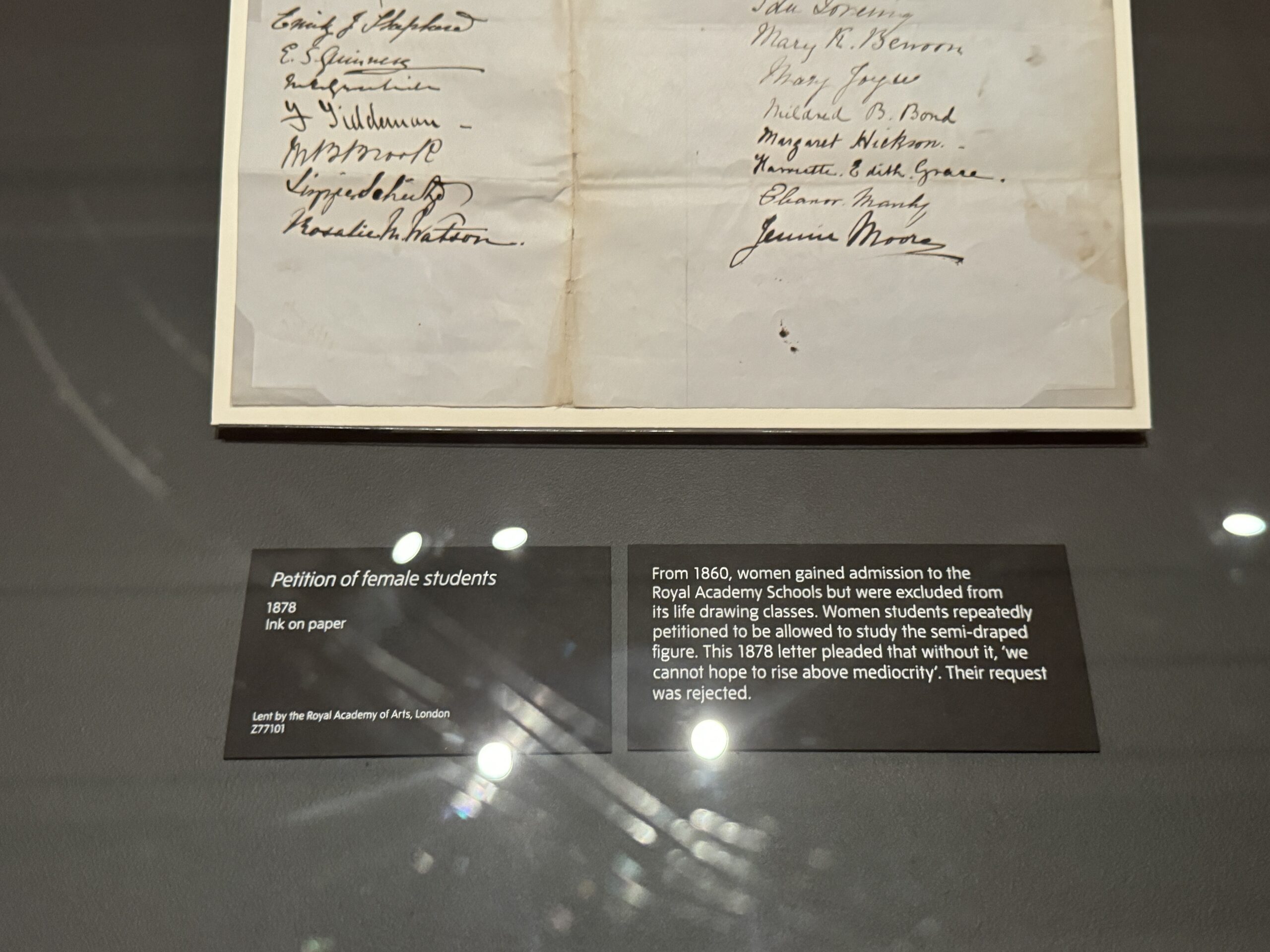

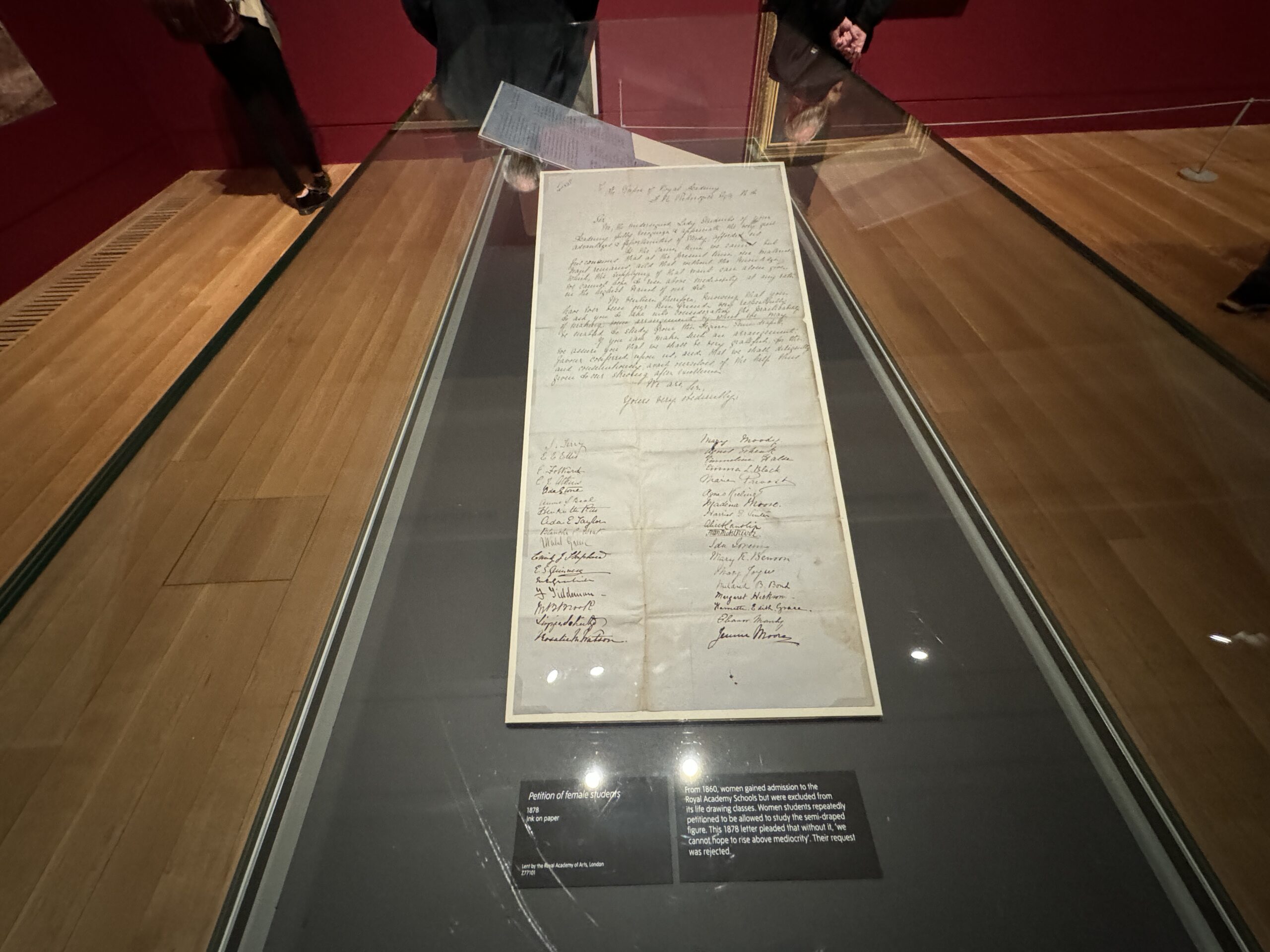

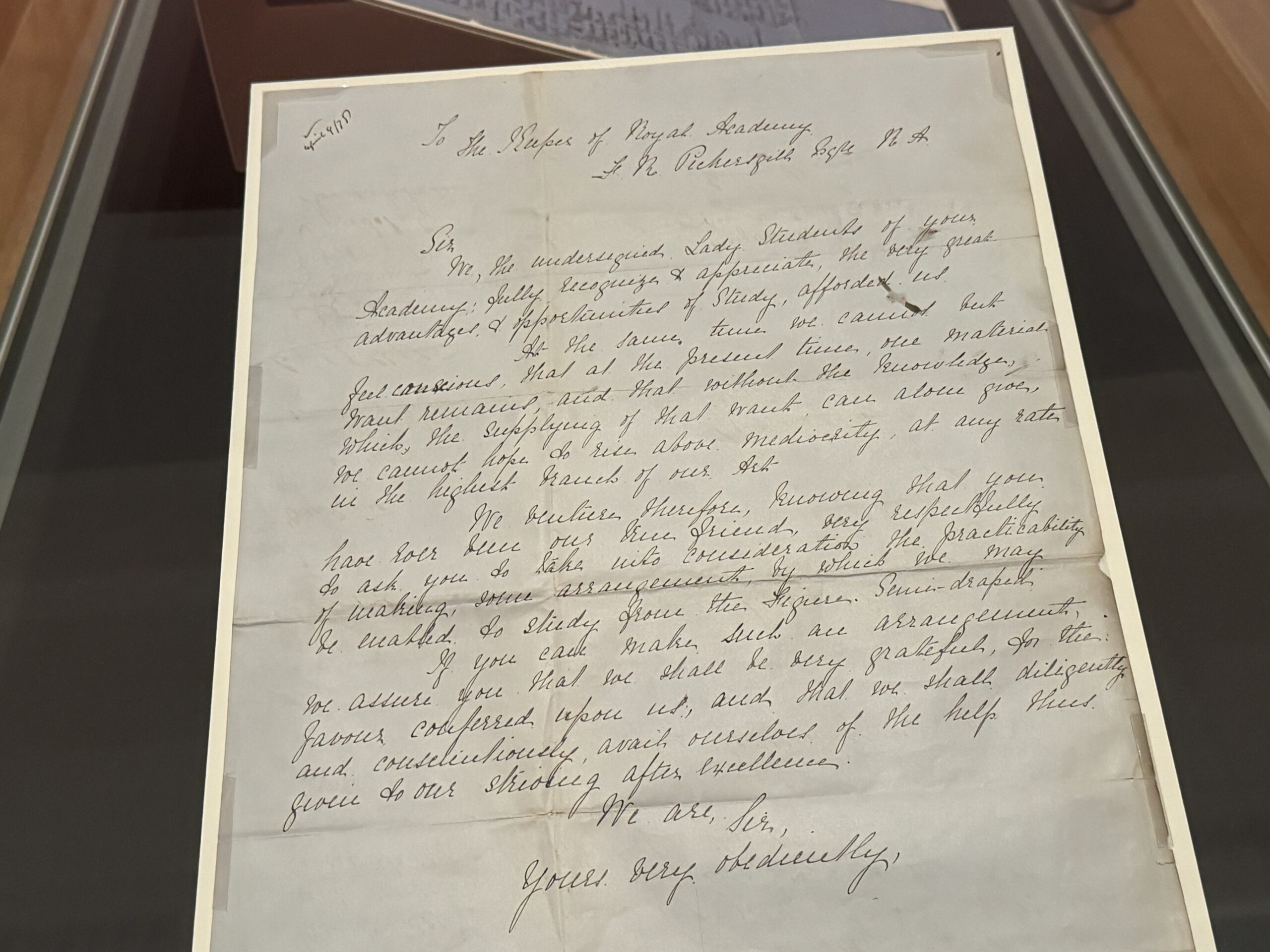

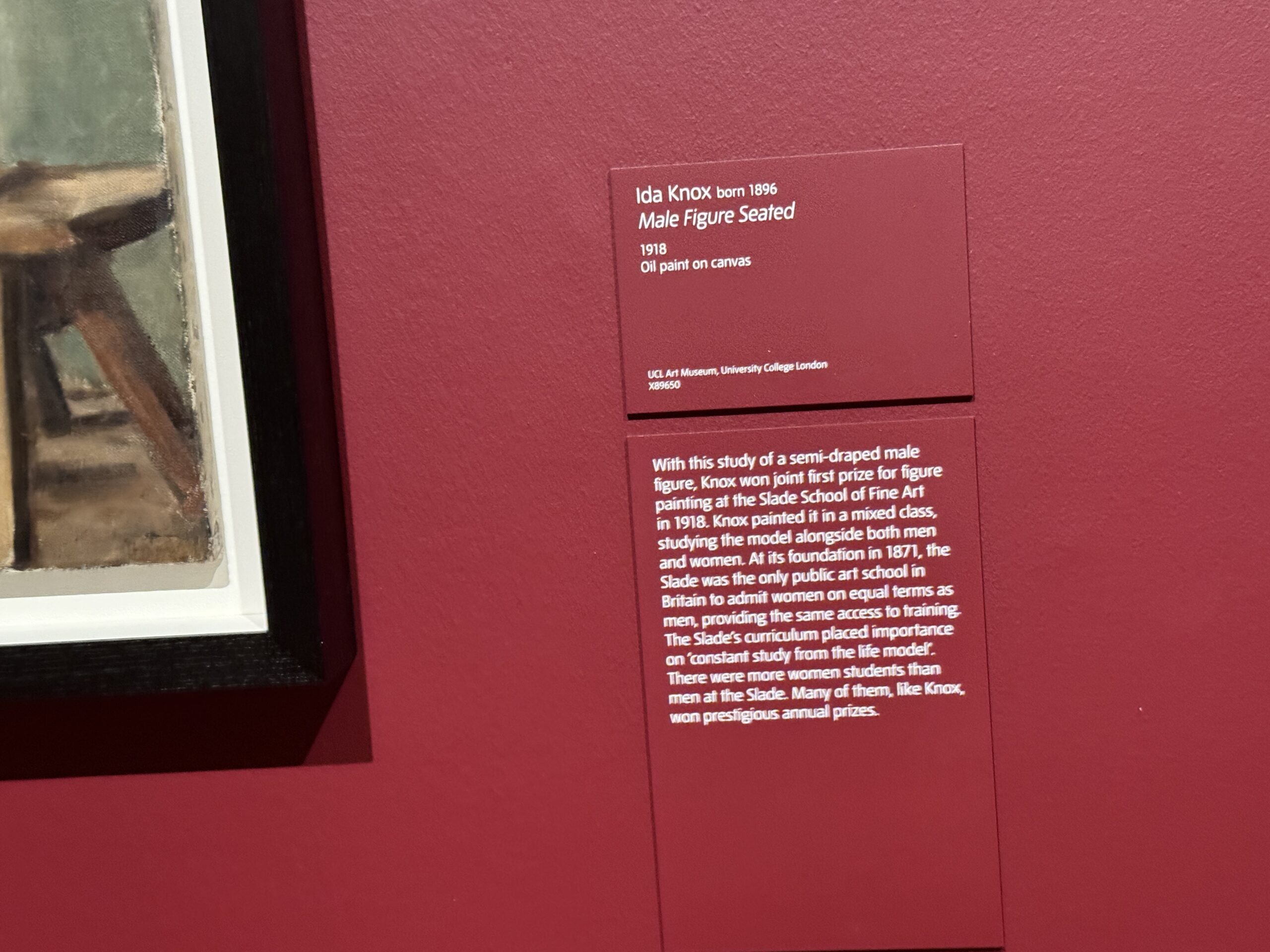

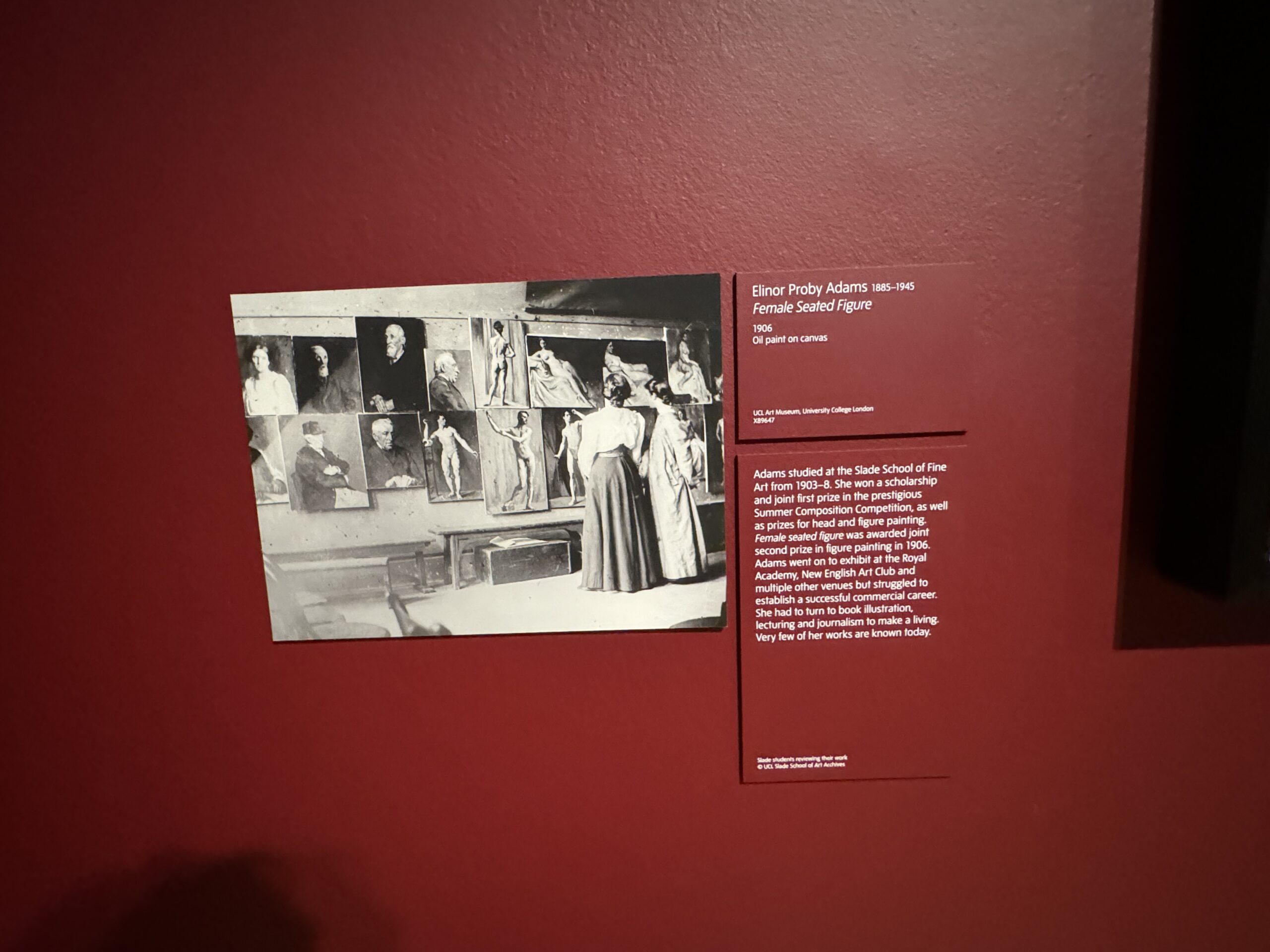

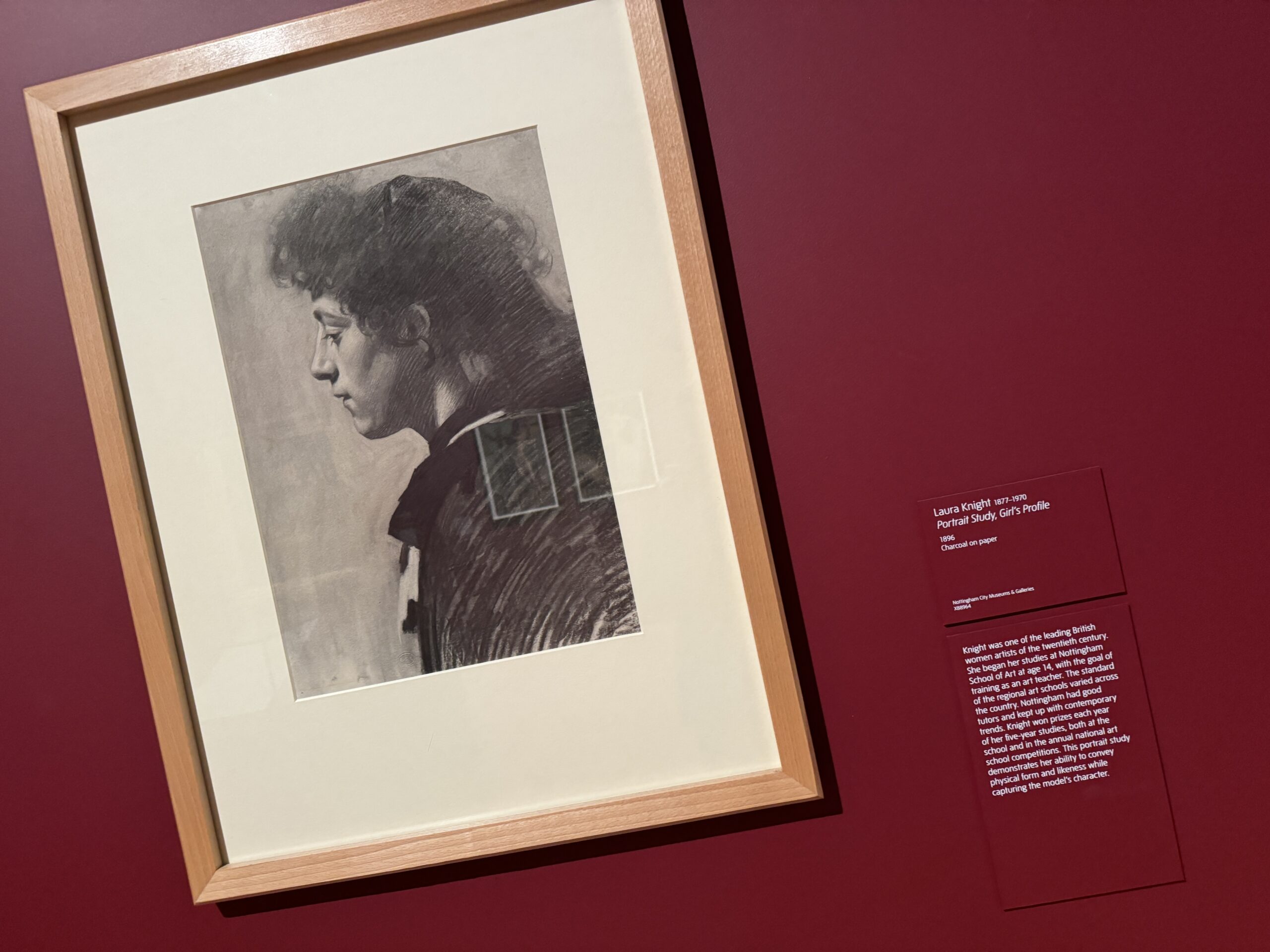

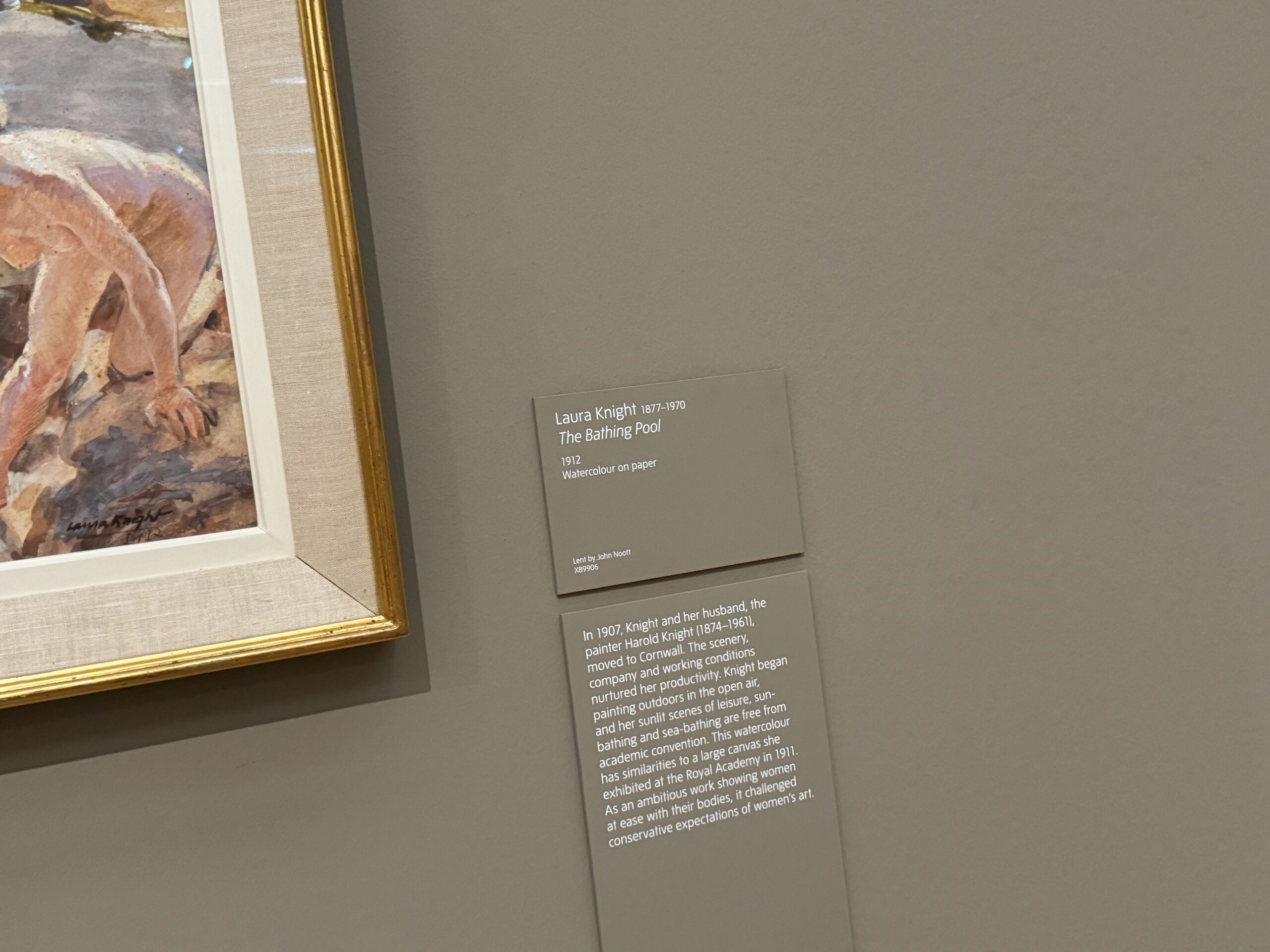

Claxton petitioned hard for the admission of women to the Royal Academy (none since Kauffman’s day), and joined the campaign for women’s right to attend life classes. A gallery is devoted to historical documents and photographs; yet the masterpiece here is not the male nude you might expect but a startling profile head in black chalk by Laura Knight.

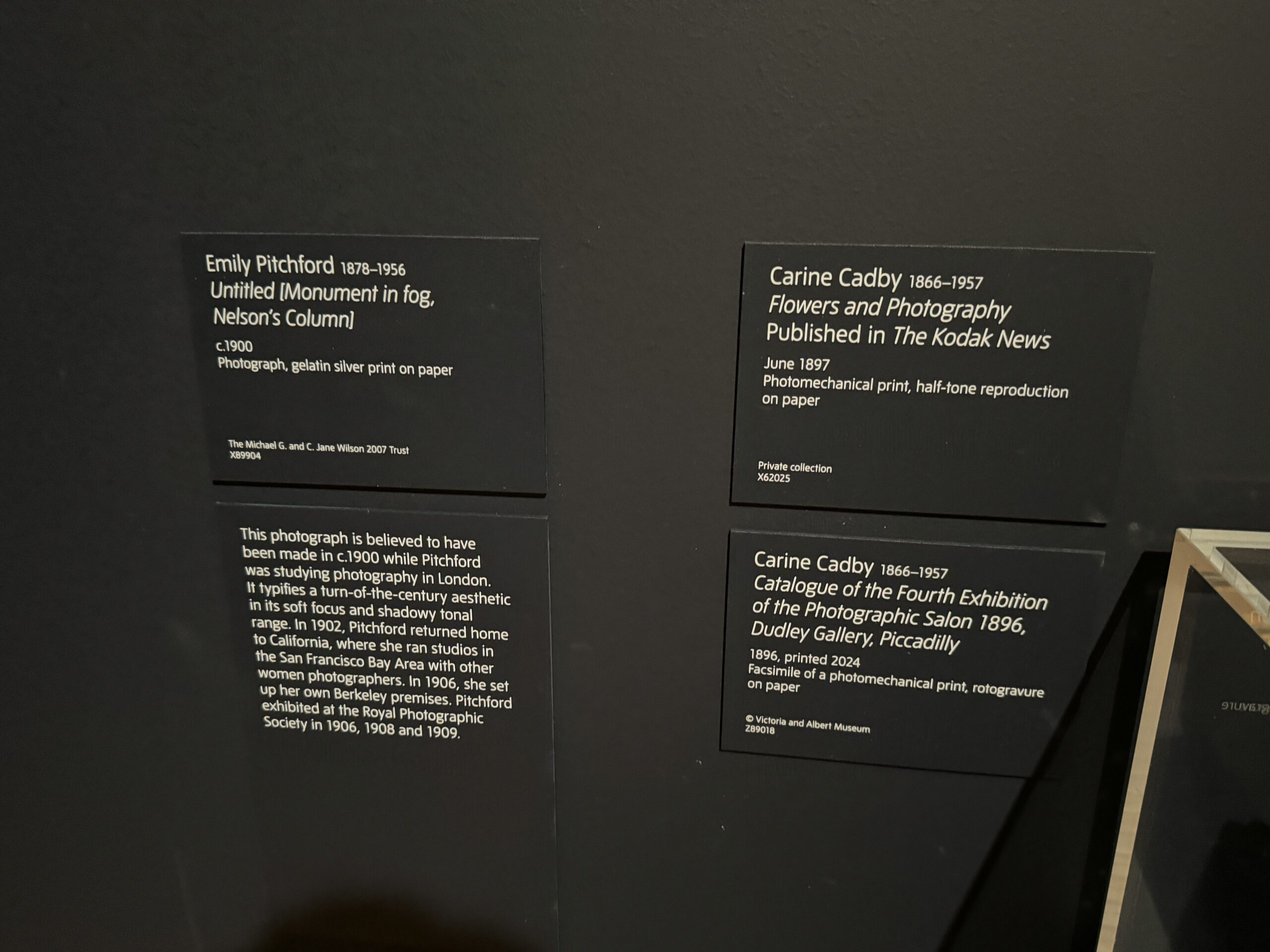

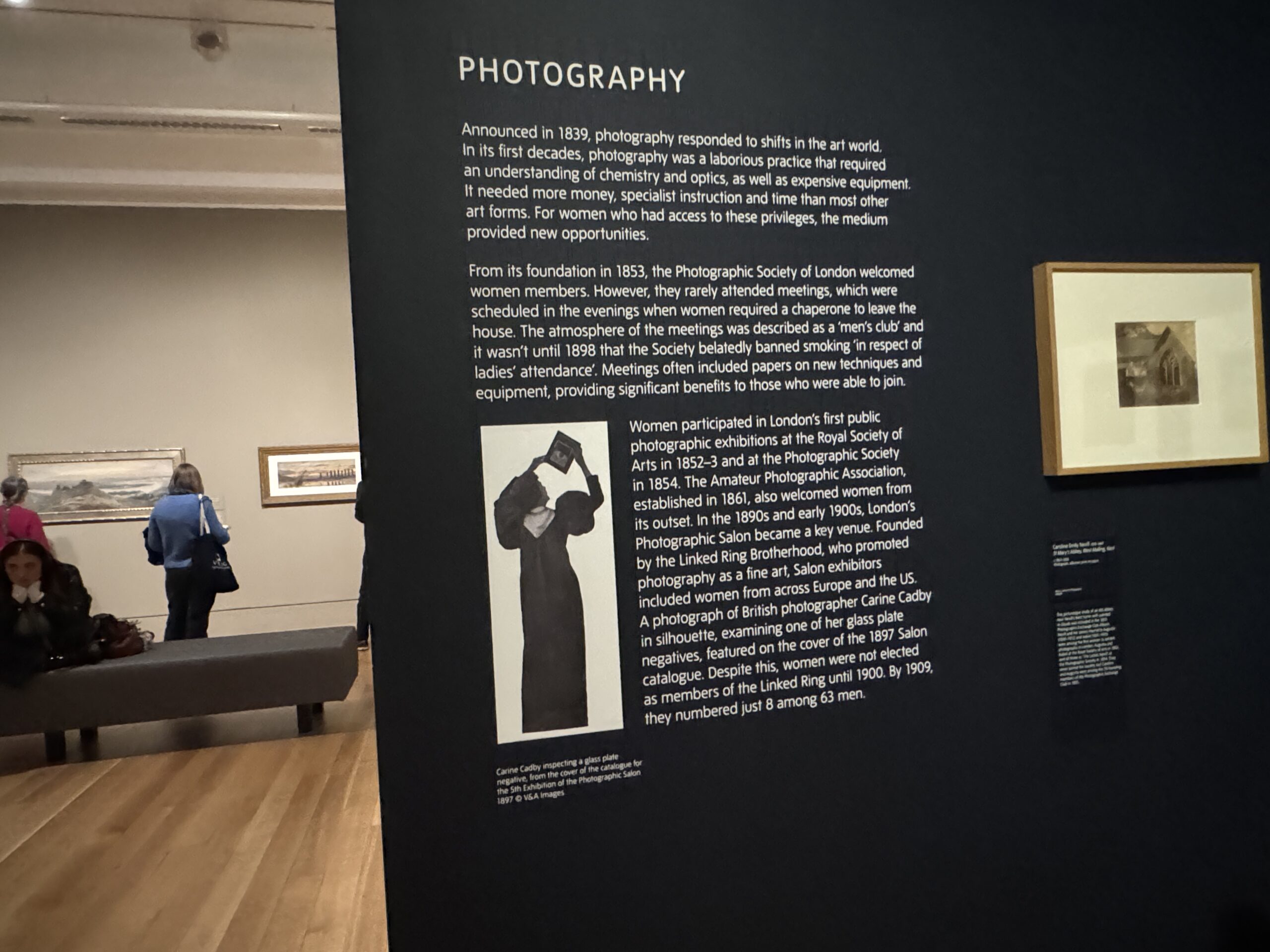

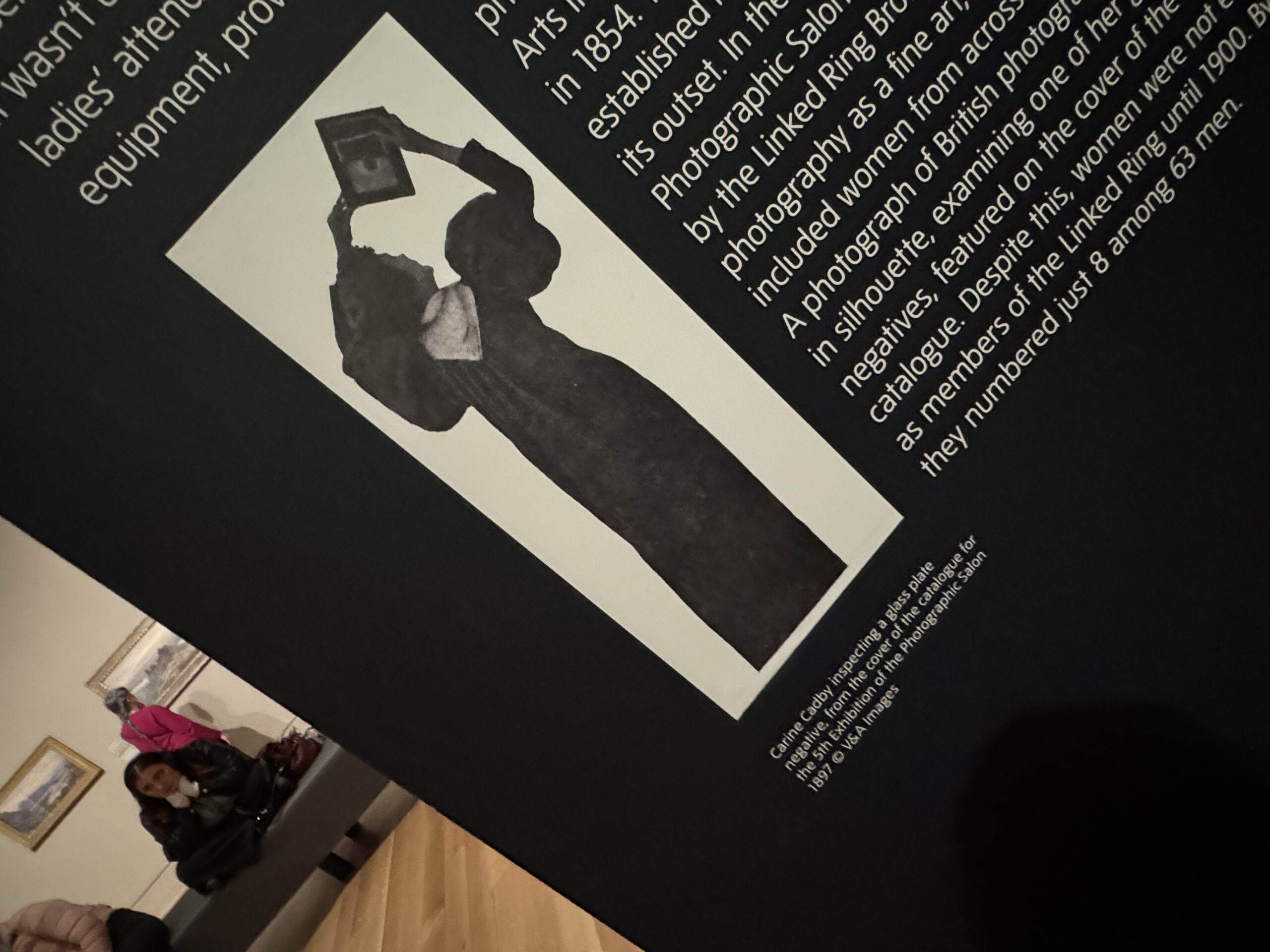

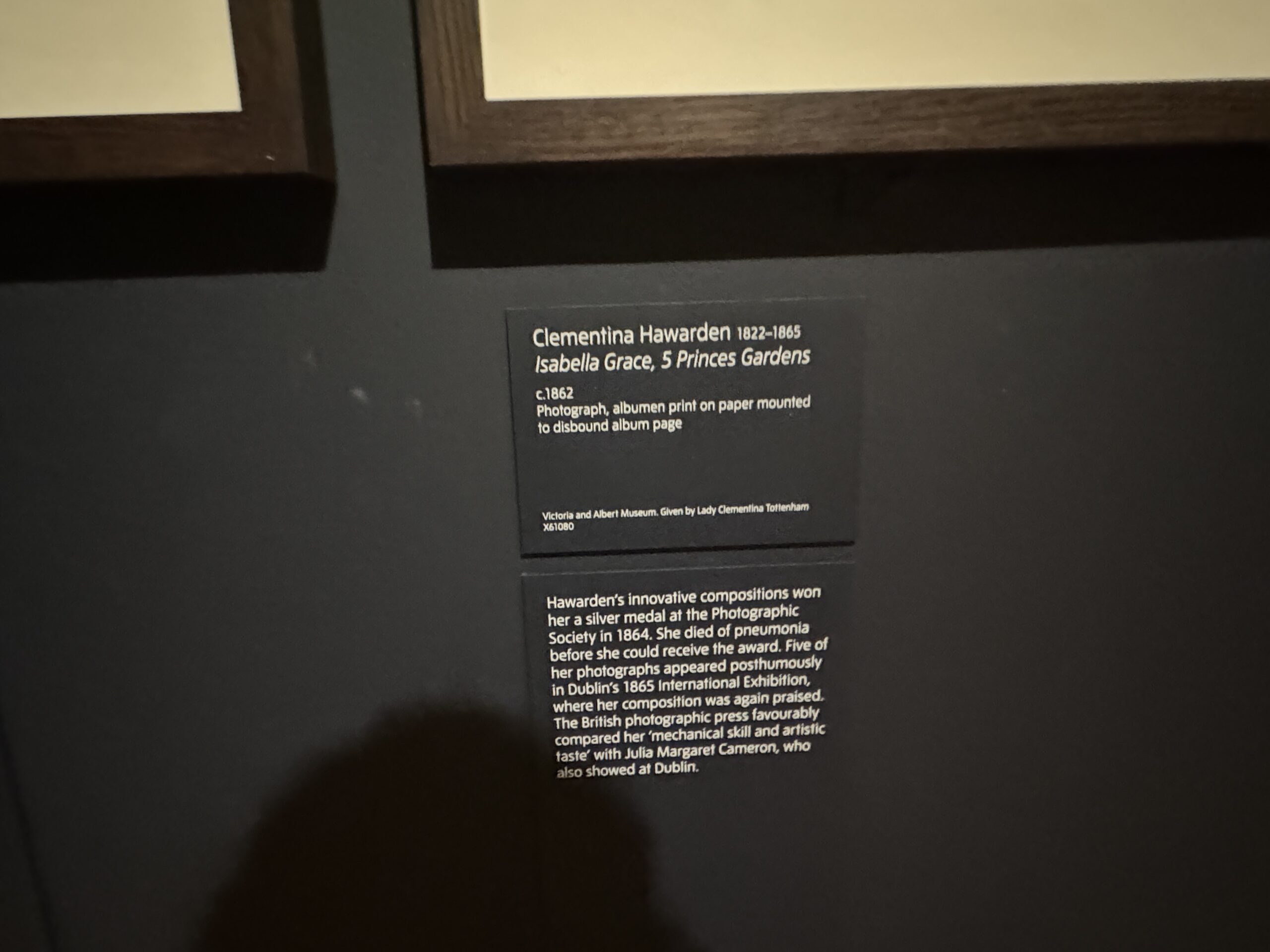

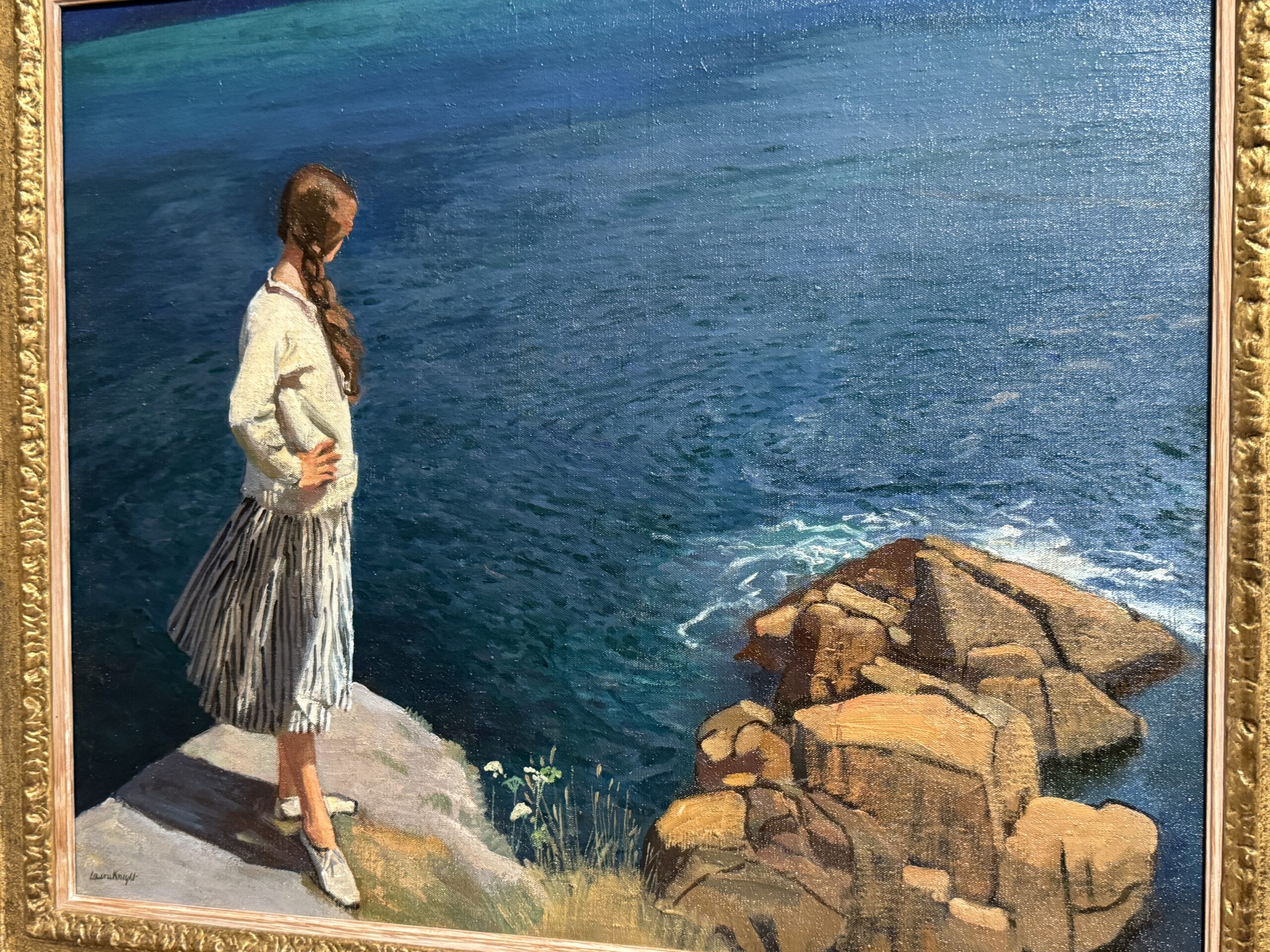

Knight is strongly represented with a sequence of cliff-edge paintings; but what about her near-namesake, Winifred Knights? The Deluge is a shattering masterpiece of British modernism, painted in 1920 and thus eligible, yet not here. And why are the ethereal and supremely original blue cyanotypes of Anna Atkins (1799-1871) missing from the niggardly photography section, along with Christina Broom (1862-1939), pioneering photojournalist, whose stirring portraits of suffragettes would have been so apt?

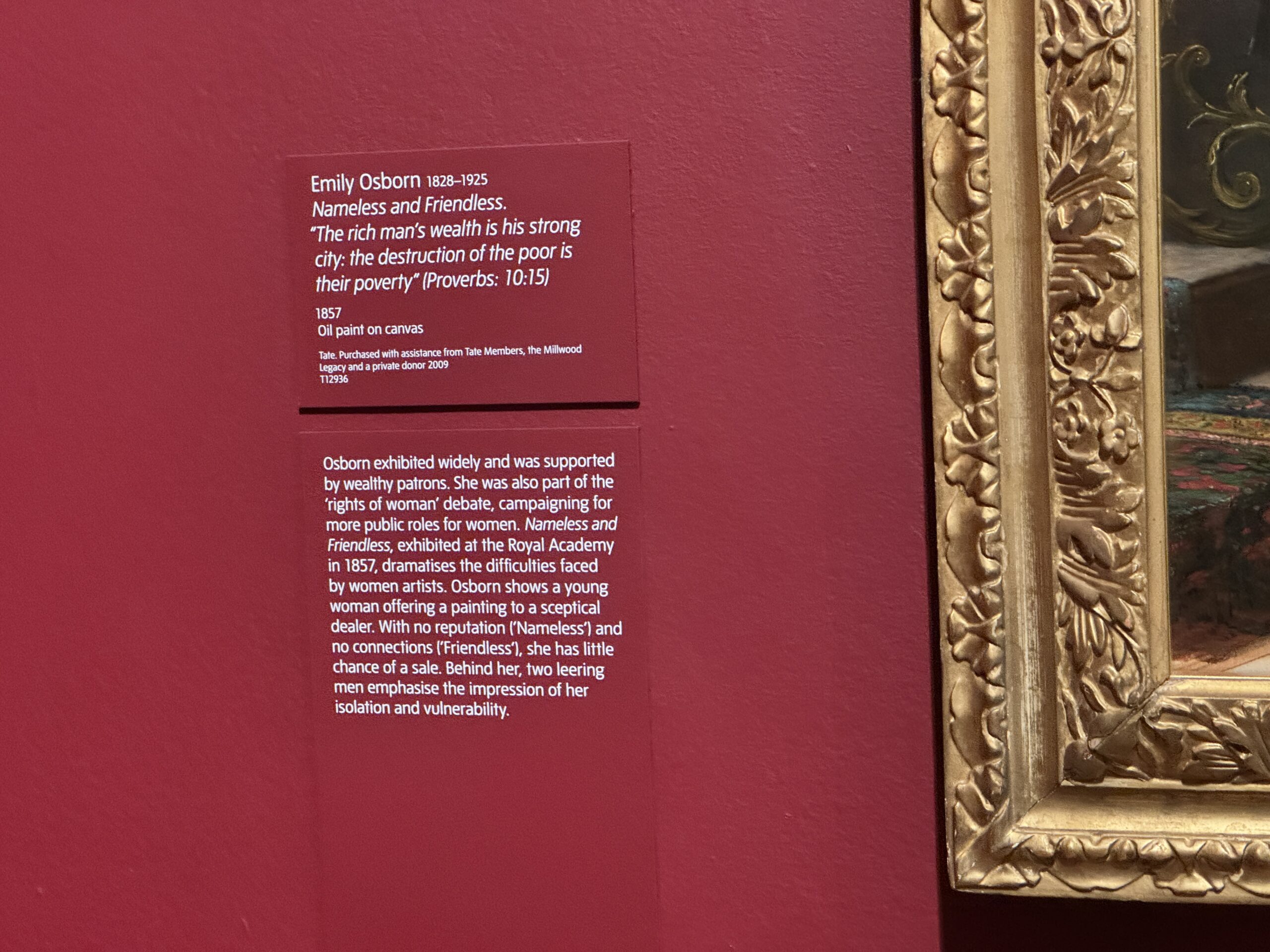

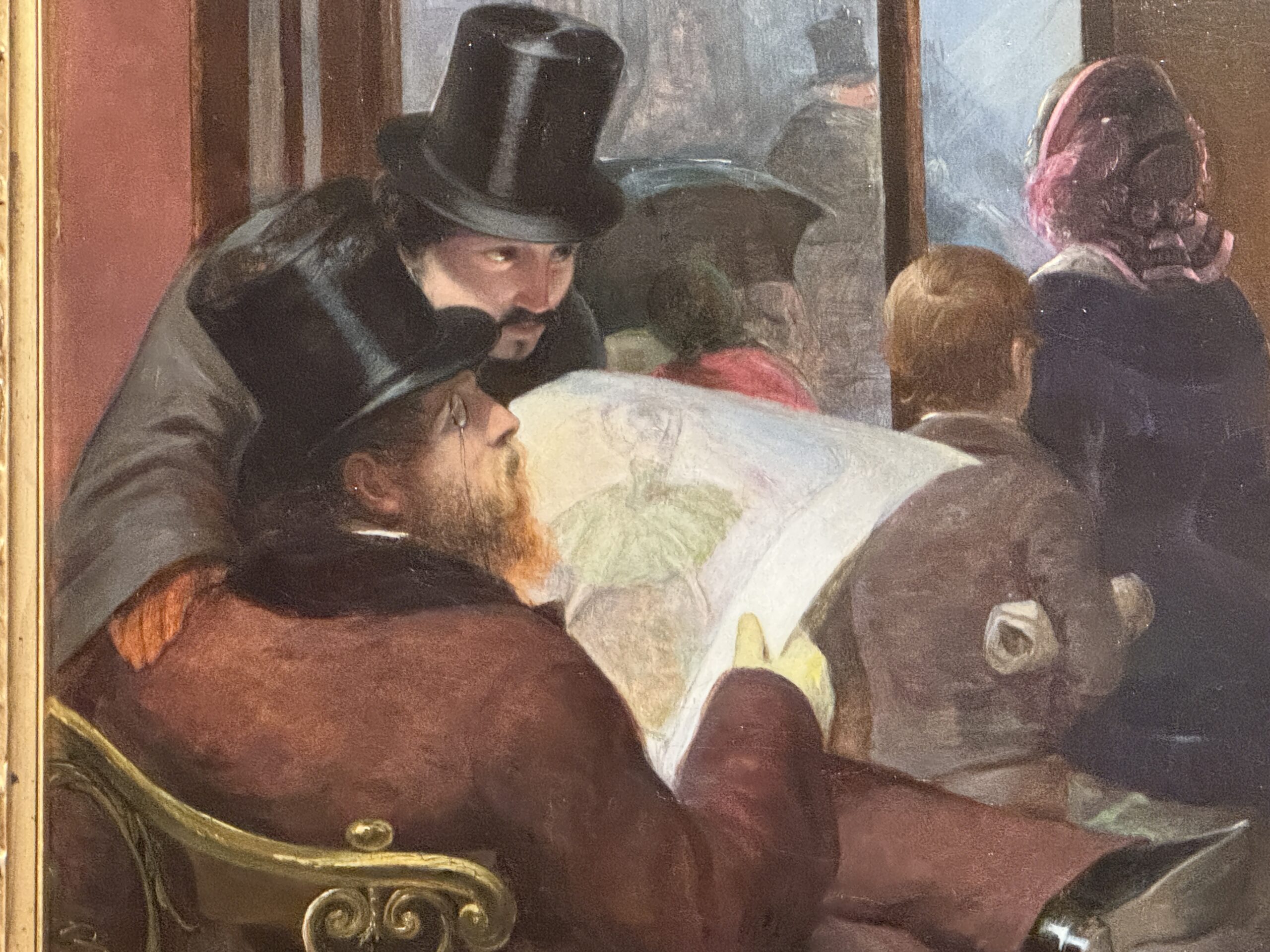

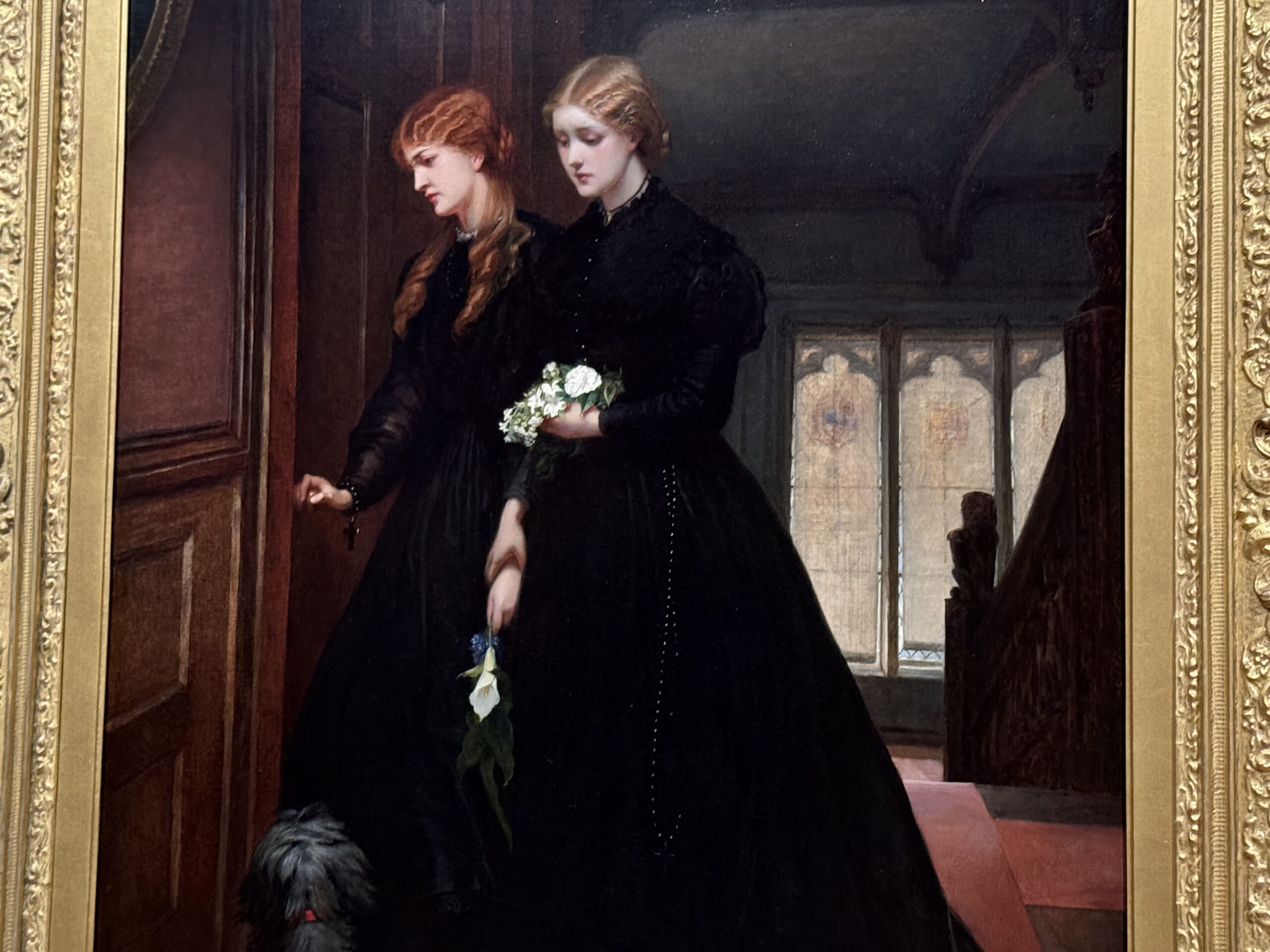

The show is thick with flowers, descending from Delany right down to Helen Allingham’s twee cottage gardens, all ready for their postcard reproductions. And if Allingham, then why not the visionary genius of Beatrix Potter? Weak pre-Raphaelite schlock fills the largest gallery, along with Victorian pieties such as Emily Osborn’s distressed gentlewoman, eyes downcast, awaiting the verdict of a dealer on her latest canvas, while two male artists leer in the background. Nameless and Friendless is terminally mawkish.

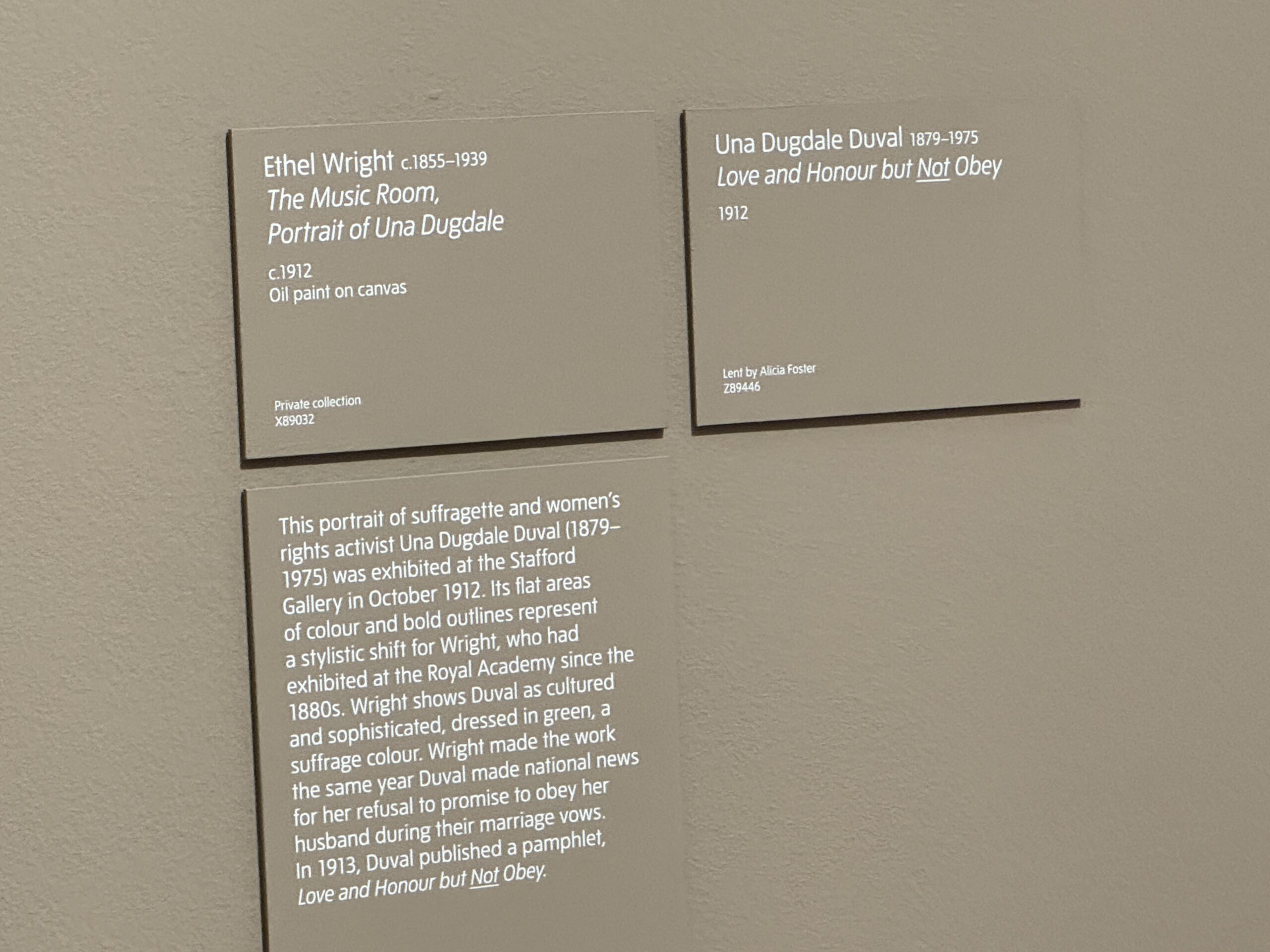

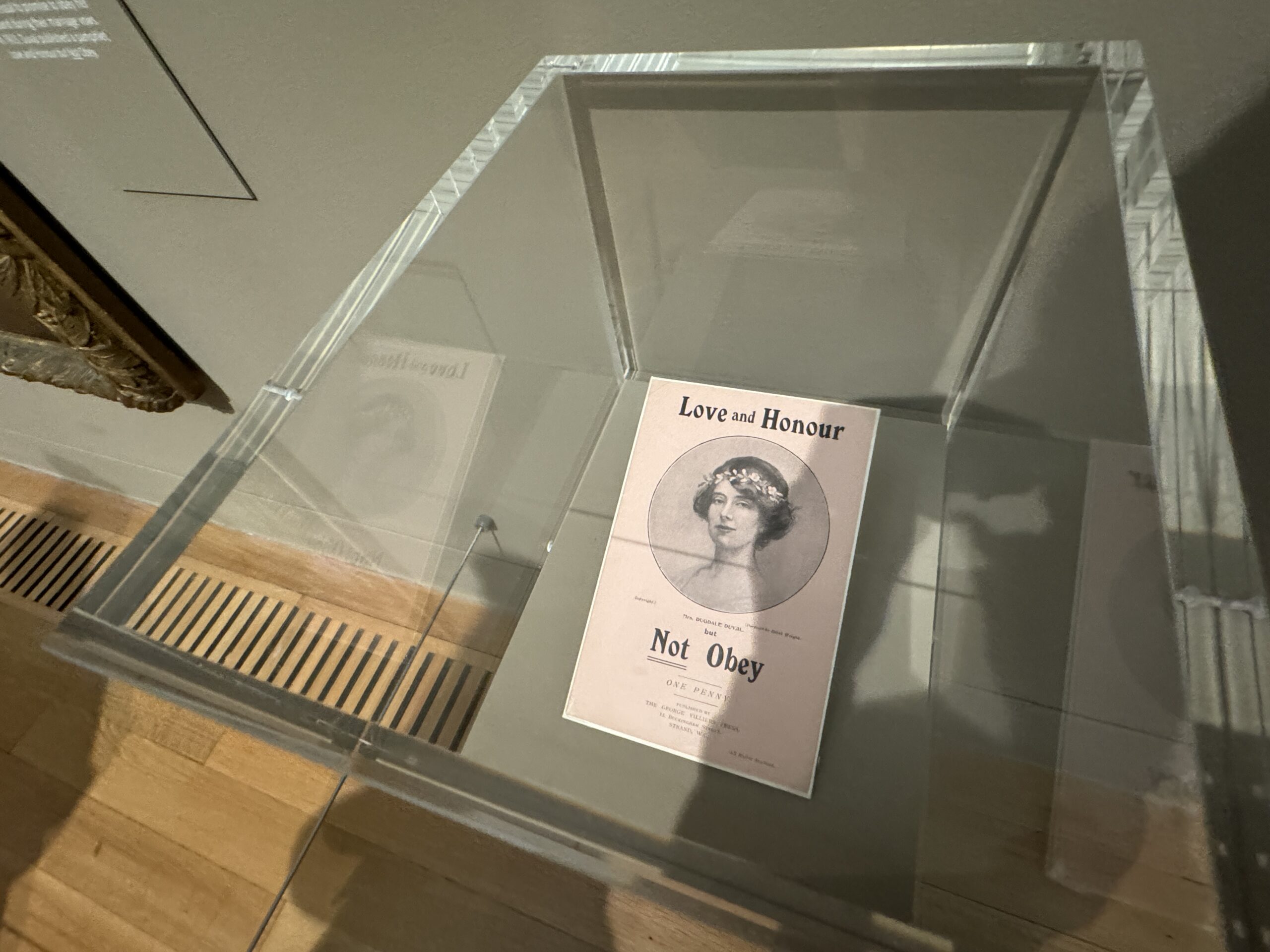

Only rarely do women’s art and women’s history spark together in this show. You see it in Ethel Wright’s fabulous 1912 portrait of the suffragette Una Dugdale Duval, in an arsenical green dress beneath a wallpaper of ludicrous fighting cocks, where Wright’s modern bravado exactly meets that of her sitter. And you see it in Gwen John’s immortal 1902 self-portrait, small and distanced, light catching her eyelashes in an atmosphere of hushed stillness, so direct and yet so self-contained: the momentous assertion of reticence.

That epochal image appears on the exhibition posters, perhaps promising too much. For even the best of the artists here are occasionally represented by the least of their works, quite apart from the mystifying omissions. The theme of Now You See Us is undoubtedly riveting. The captions (and the excellent catalogue) are superbly written. But art is trumped by social history too often in this show, words overshadowing images.

thepersistent.com Below the Surface of Women’s Art, Centuries of #MeToo, Misogyny— Anne Quito,

Can an assemblage of polite portraits, sentimental botanical prints, and charming “needlepainting” say something new about women’s efforts to be taken seriously as artists?

An exhibition at London’s Tate Britain, Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920, aspires to do just that, showcasing 200 works by women who forged artistic careers in spite of the societal expectations of their time.

Curators have indeed gathered some fascinating works, but—dare we say it—is the theme a little done?

Enough to create change?

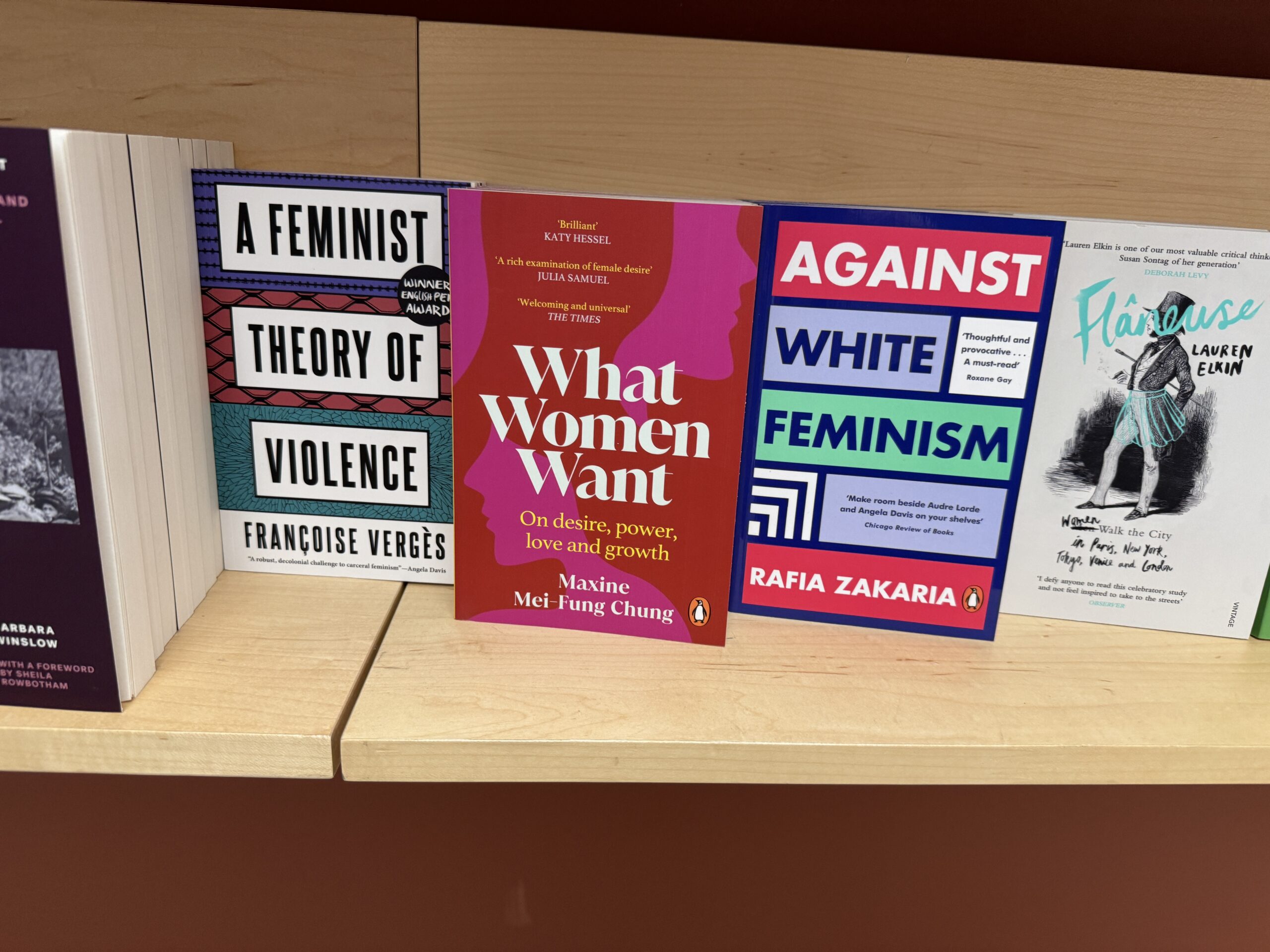

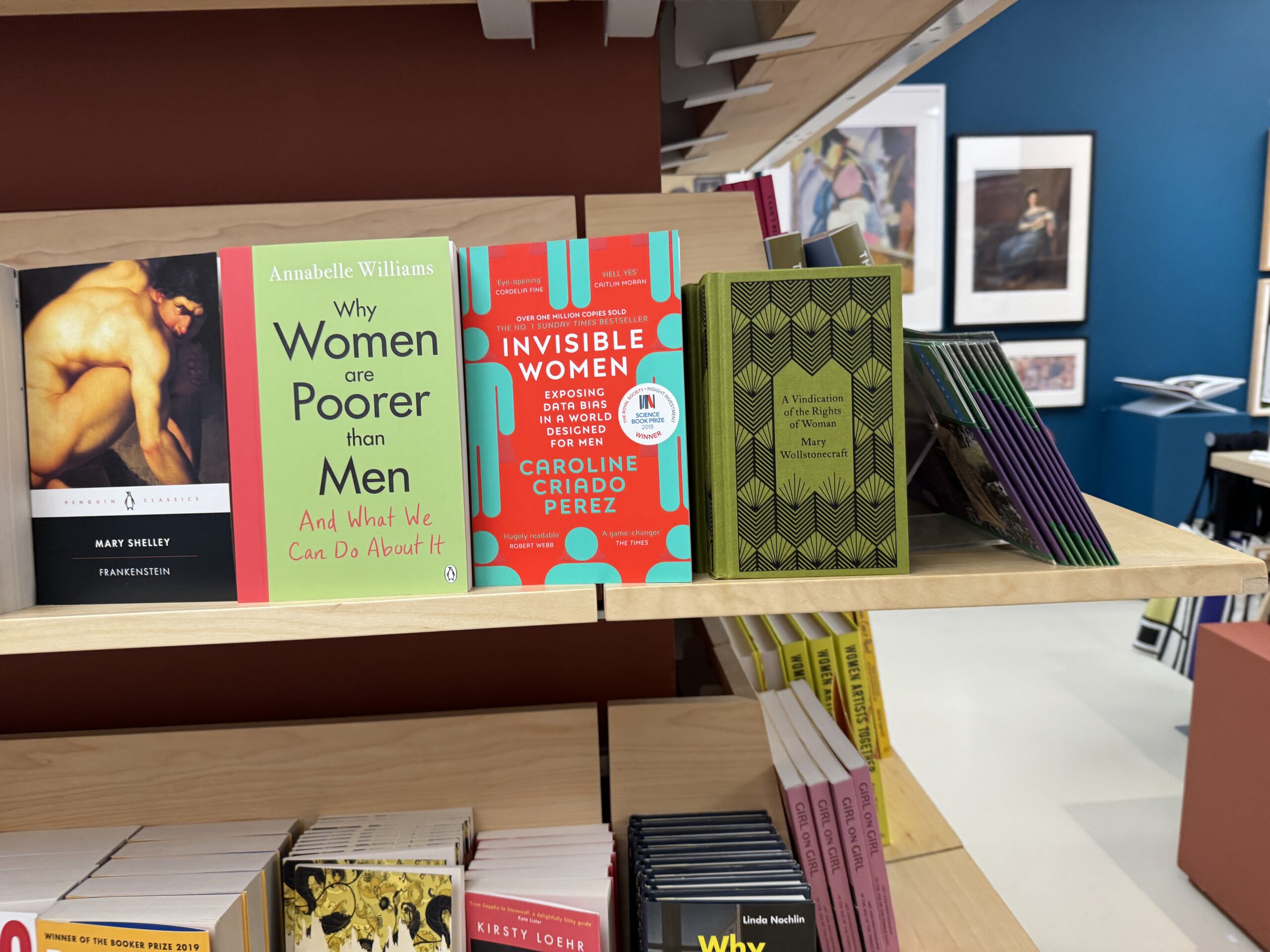

A woman’s group show is hardly a new idea, or in itself a very compelling one. The first all-female international art exhibition was held almost half a century ago, in 1976, and since then curators have been recycling this premise with little variation. The forgotten women, the overlooked women, the erased women—we’ve heard it all before. Even Linda Nochlin, the feminist scholar who wrote the foundational 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” suggested in her writing that merely showing more examples of works by under-appreciated women—technically superior though they may be—isn’t enough to create change.

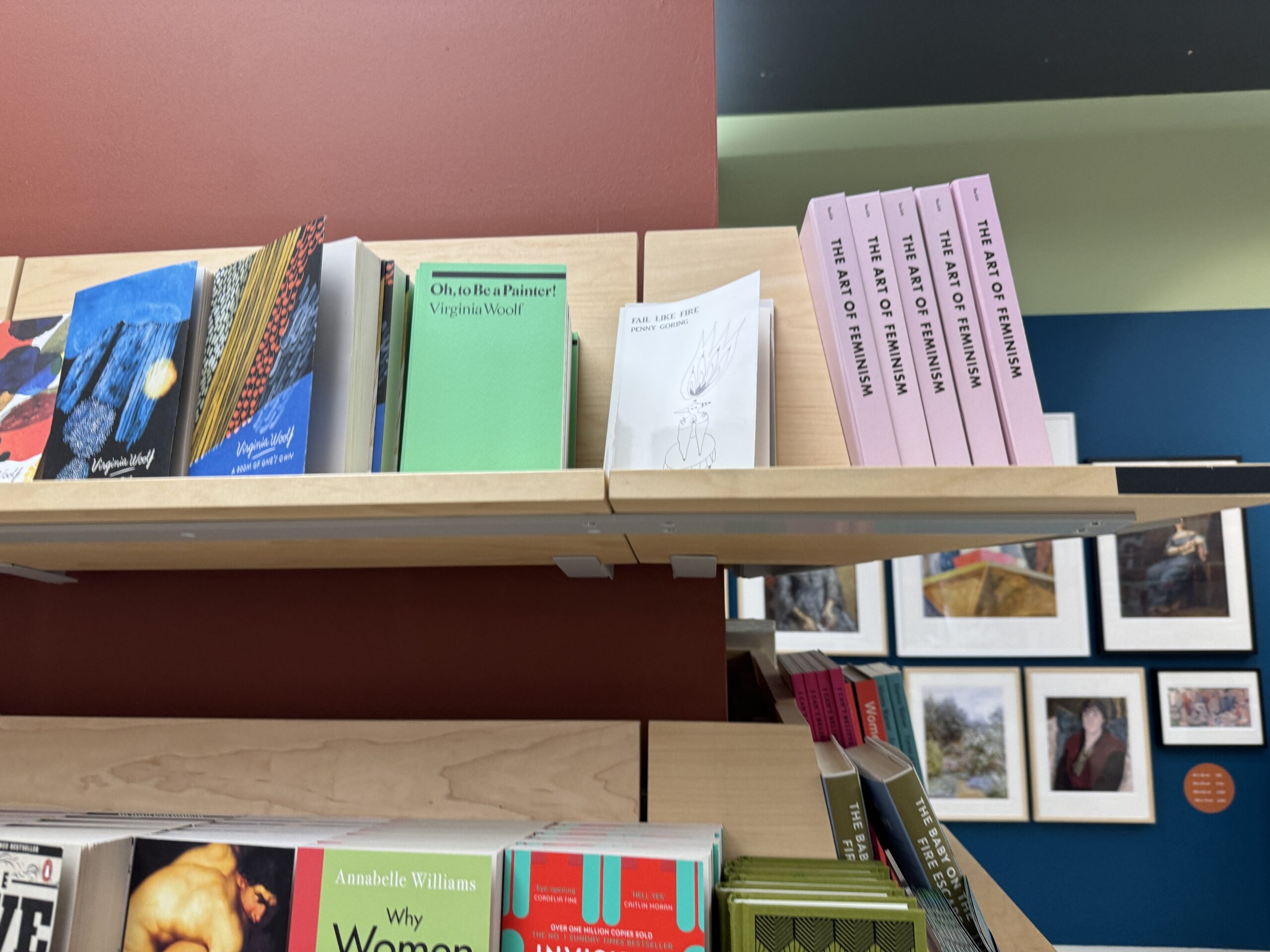

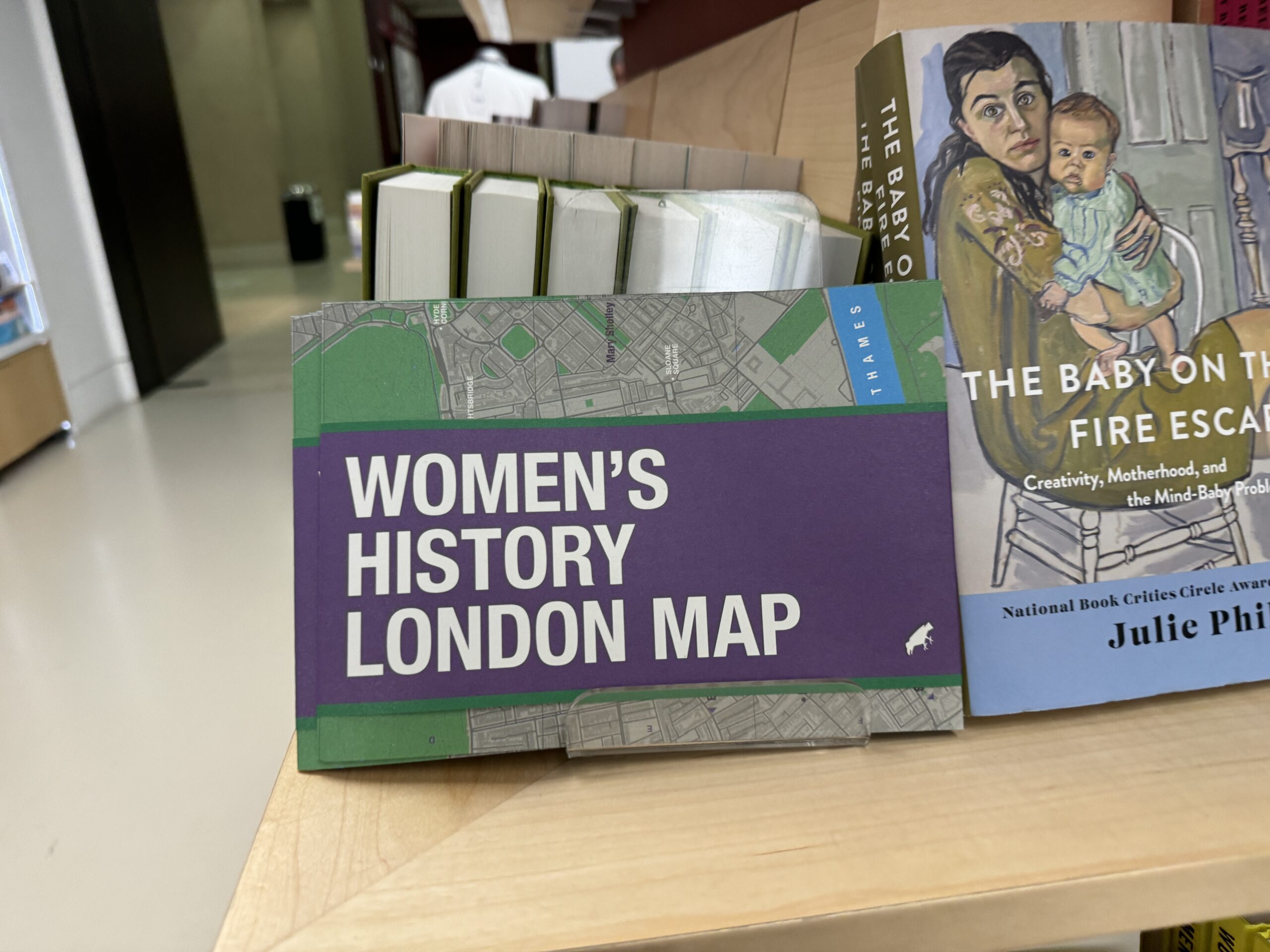

But the Tate insists that the appetite for such a show is healthy as ever. “You only need to look at the popularity of other shows of women artists around the world, as well as the explosion of books, podcasts and articles around the subject, to see that there’s a high level of interest in revisiting what we think we know about women artists of the past,” explains Tabitha Barber, the museum’s curator of British art, 1500–1750, in an interview with The Persistent.

Barber adds that the impressive attendance records for the Tate’s recent blockbuster show, Women in Revolt! Art, Activism and the Women’s movement in the UK 1970–1990, indicate the public’s enthusiasm for the subject. But the appeal of Now You See Us is more subtle.

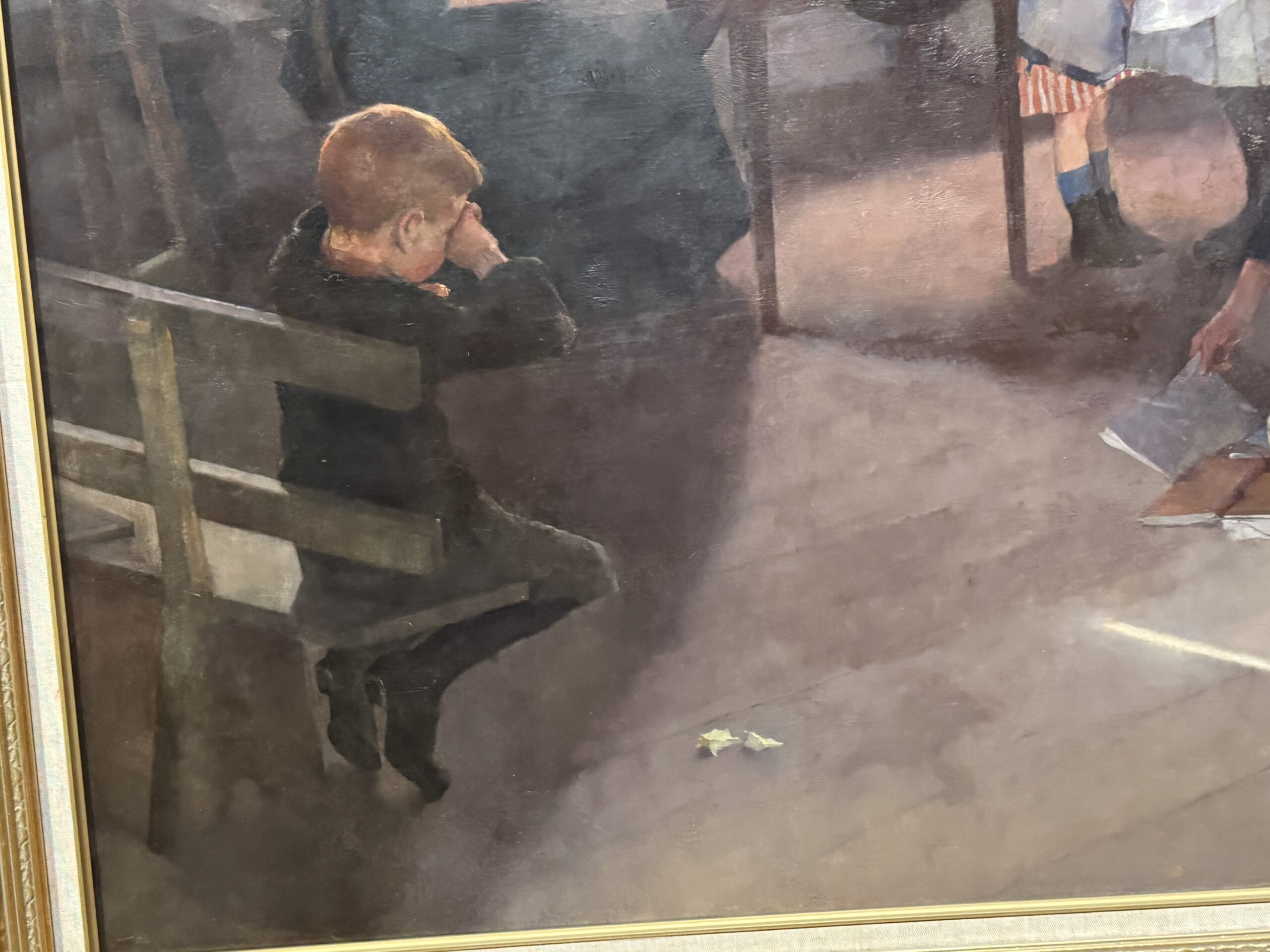

In lieu of radical (and Instagrammable) feminist art, we have traditional works that invite viewers to pause, to linger, to probe a little. The reward is a journey beyond the often-polite compositions that invites the viewer to question, well, everything. This isn’t a simple ask at a time when the typical museum visitor spends less than 30 seconds looking at a work of art.

Those who do take the time to look closer at Now You See Us will uncover a great deal about the plight of professional women artists over the last 400 years.

“No women could paint”. Take Artemisia Gentileschi, among the most celebrated of the baroque artists, who was raped by her tutor at age 15. Her painting, Susanna and the Elders, which is included in the exhibition after extensive restoration work, depicts the tale of a young married woman harassed by two lecherous men who saw her bathing, and threatened to shame her publicly if she refused their advances. The Old Testament story has been painted many times over since the 3rd Century, but Gentileschi’s treatment has been praised by scholars as the rare depiction of the biblical tale to truly capture the woman’s anguish. Gentileschi’s backstory tells us why.

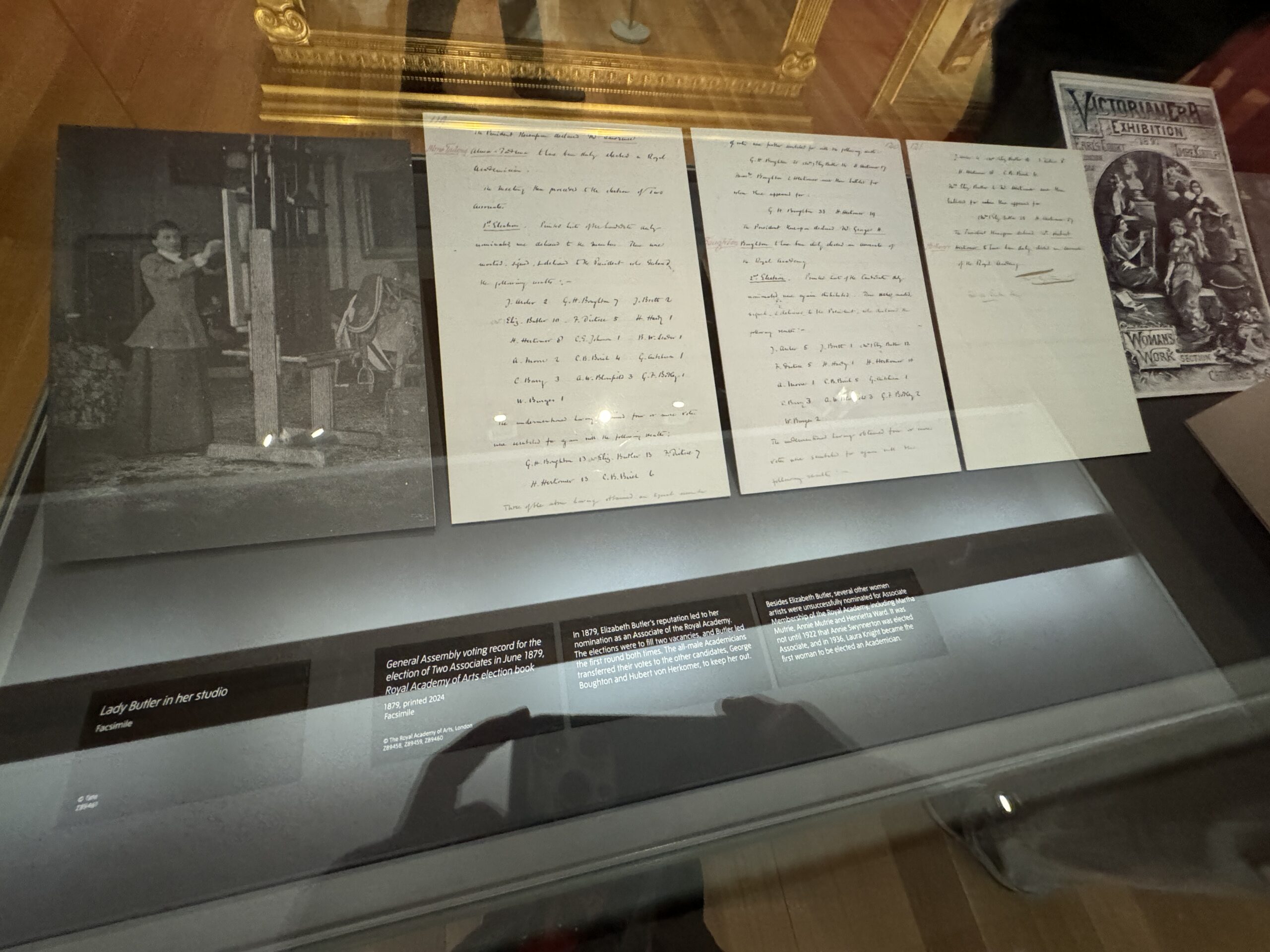

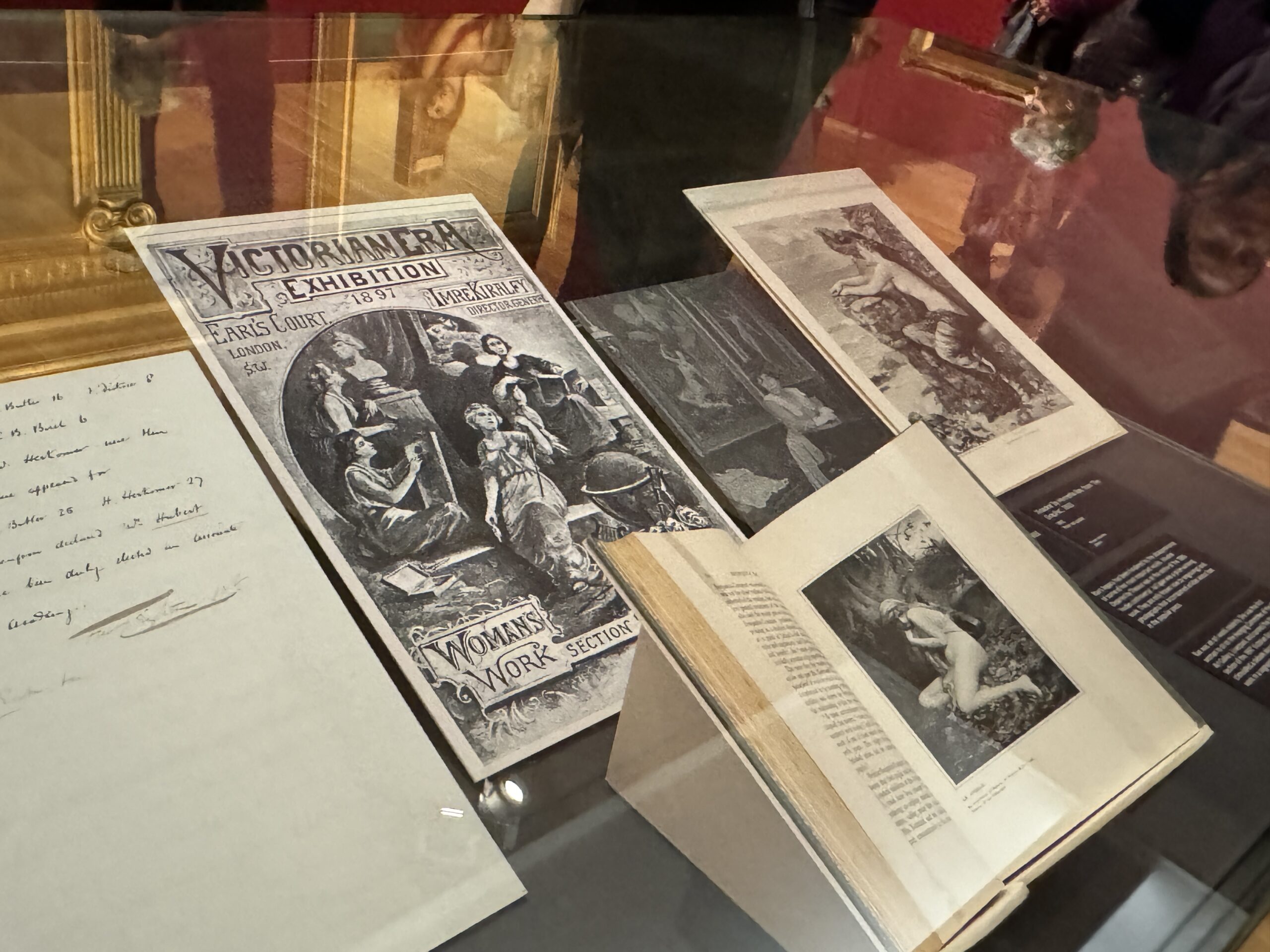

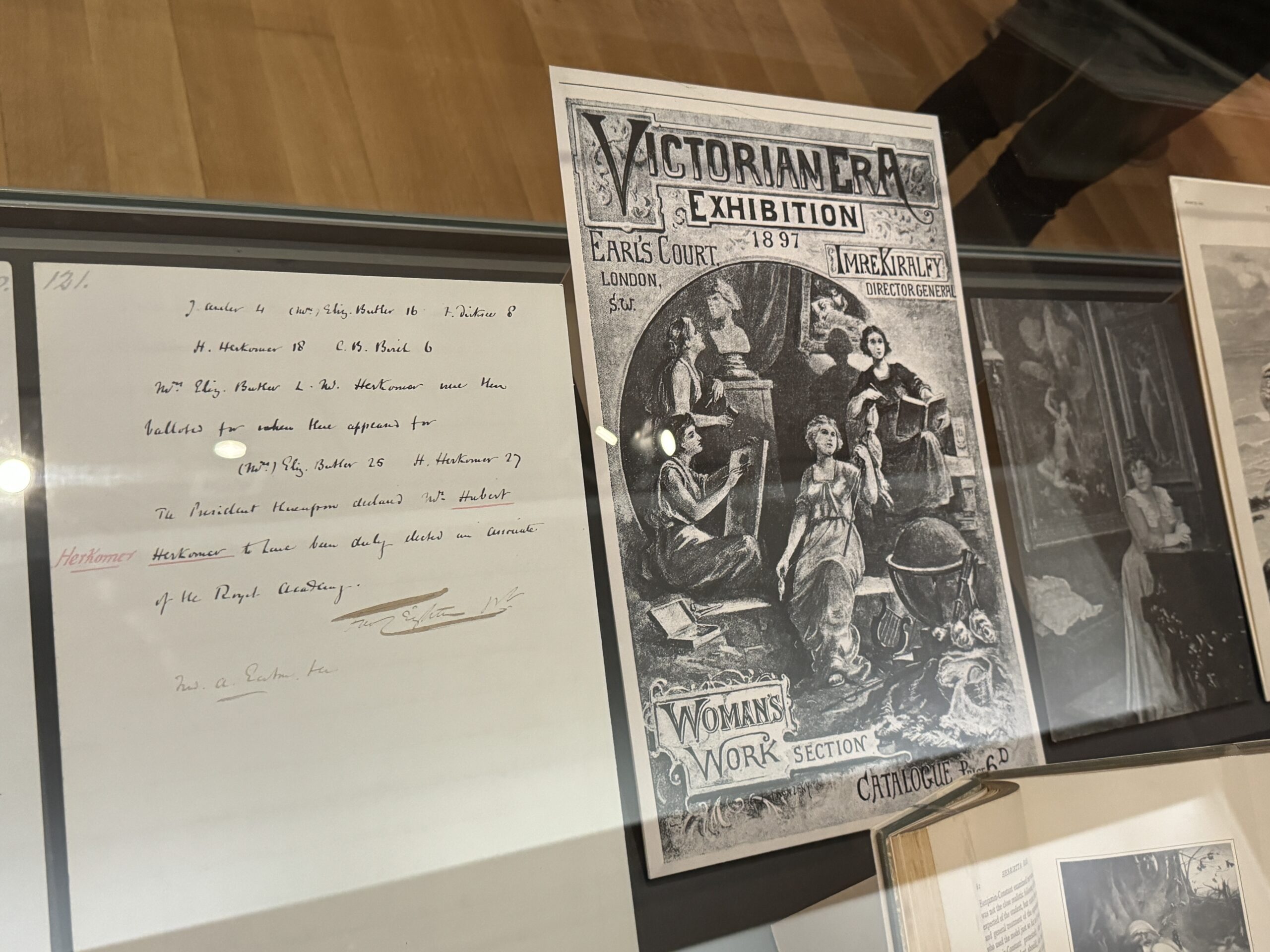

The show also includes The Roll Call, a searing war tableau by Elizabeth Thompson Butler, which the artist was inspired to paint after reading Alexander William Kinglake’s book «Invasion of the Crimea.» When it was accepted into the Royal Academy’s summer show in 1874, so many people flocked to see the painting that police had to hold back the crowds. Fellow artists gave it a standing ovation, while the influential art critic John Ruskin was moved to reconsider his assertion that “no women [sic] could paint.”

That wasn’t enough for the then all-male Royal Academy, which still refused to welcome Butler into its ranks. Butler’s career eventually took a back seat after she married an officer of the British Army, and raised their six children.

It’s storytelling that allows us to chip away at Nochlin’s original provocation. But the questions nevertheless remain: Why are there so few great female artists? Why do they remain under-appreciated?

Male gatekeepers of the art world

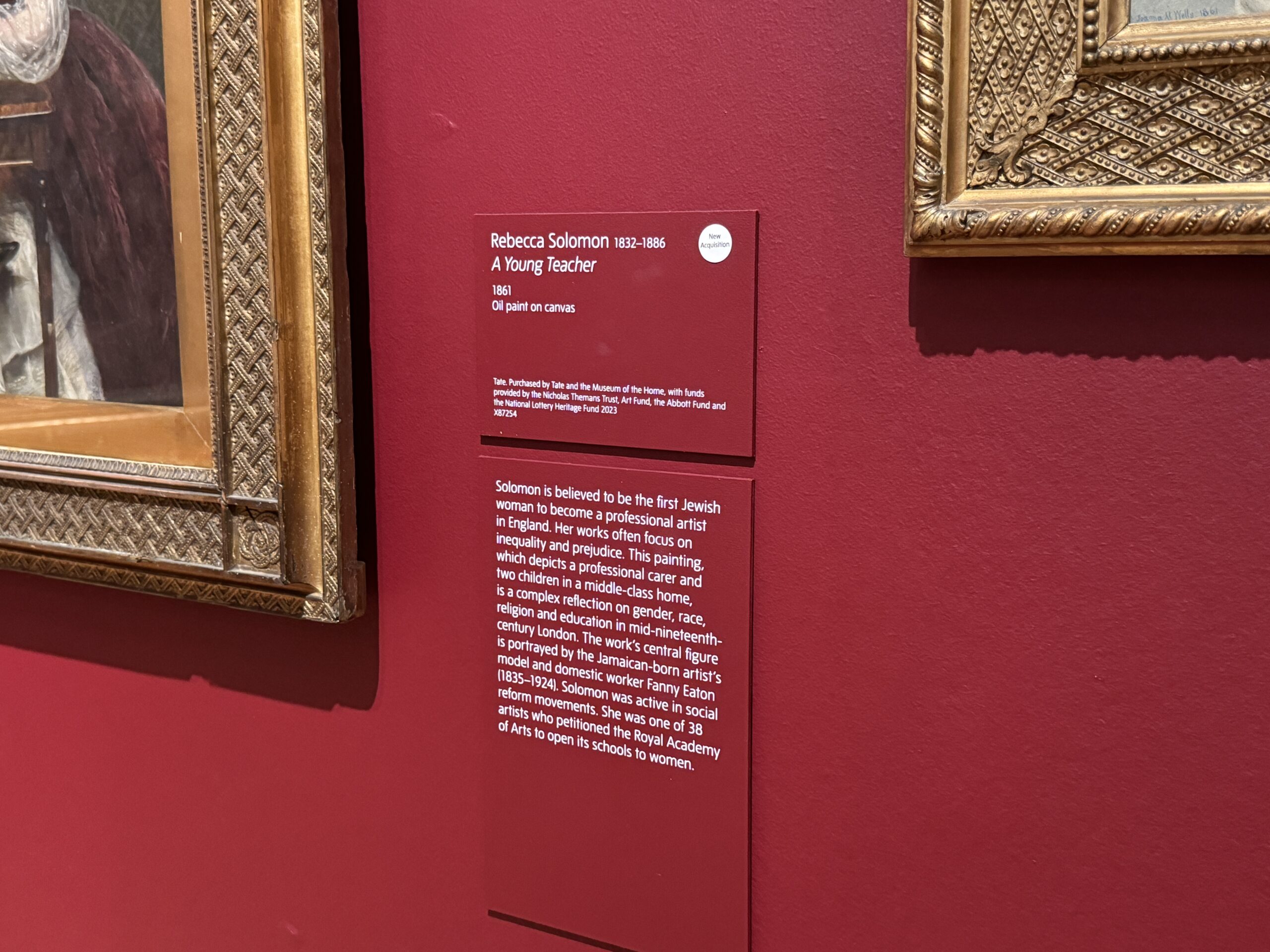

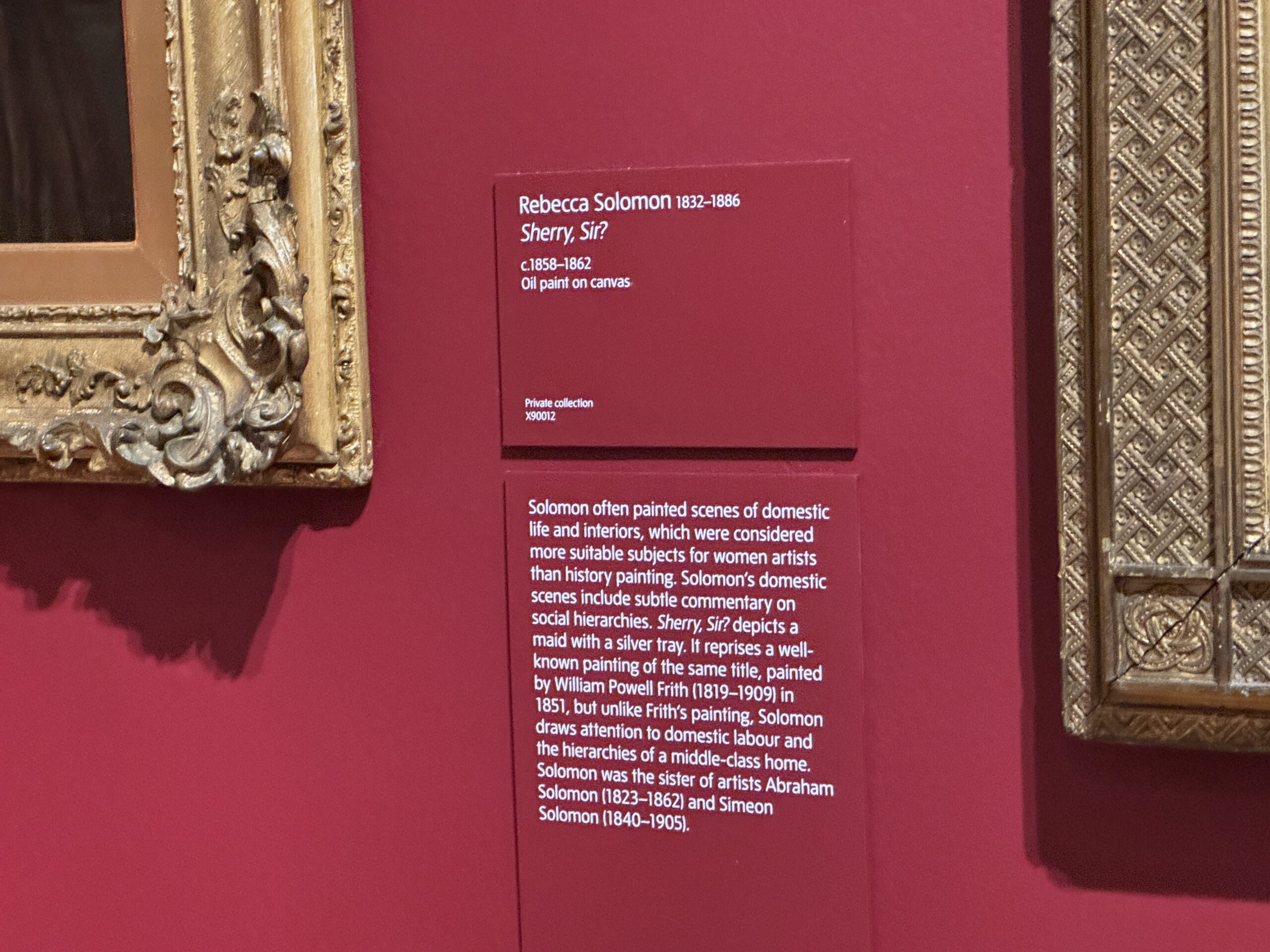

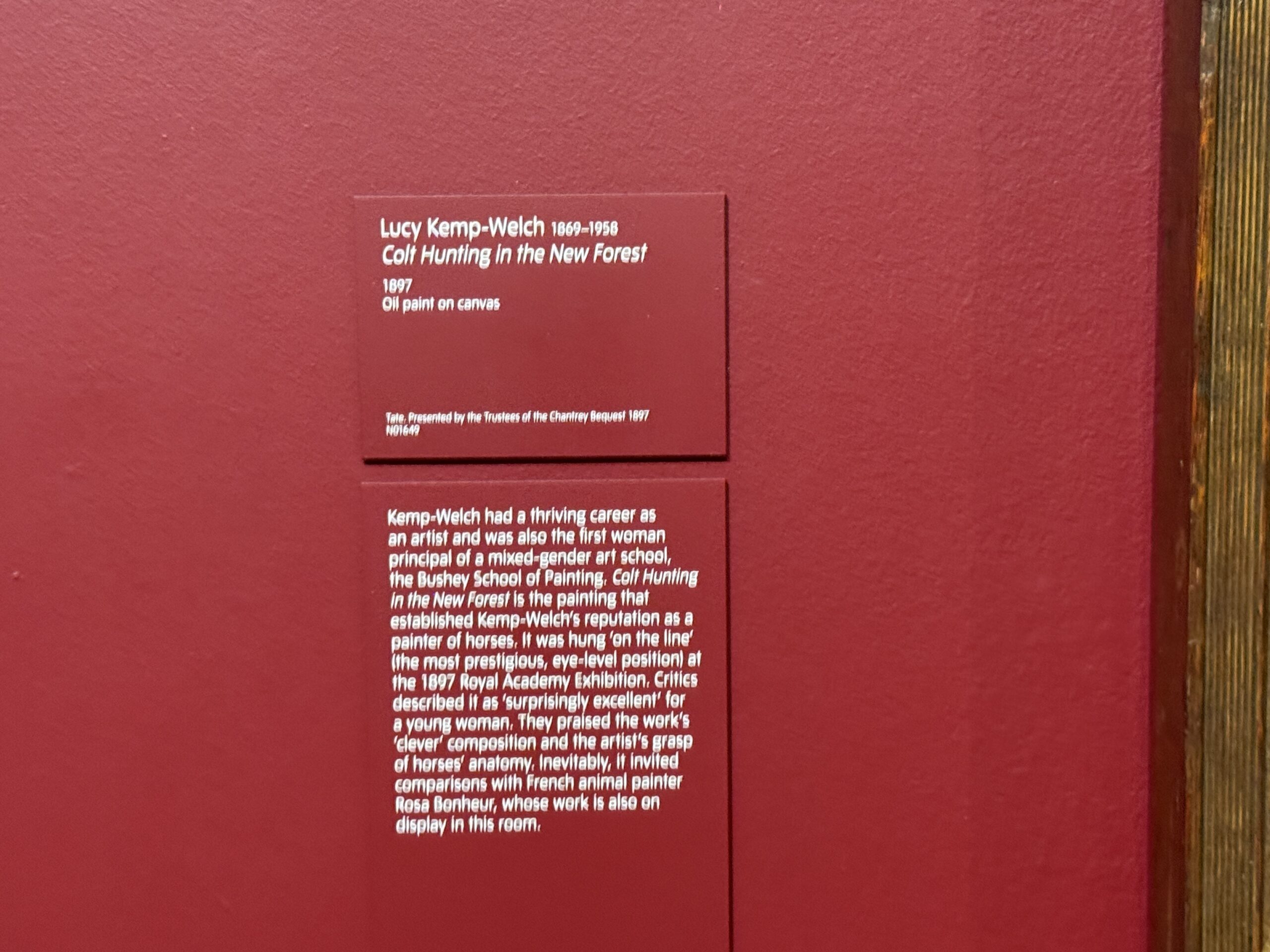

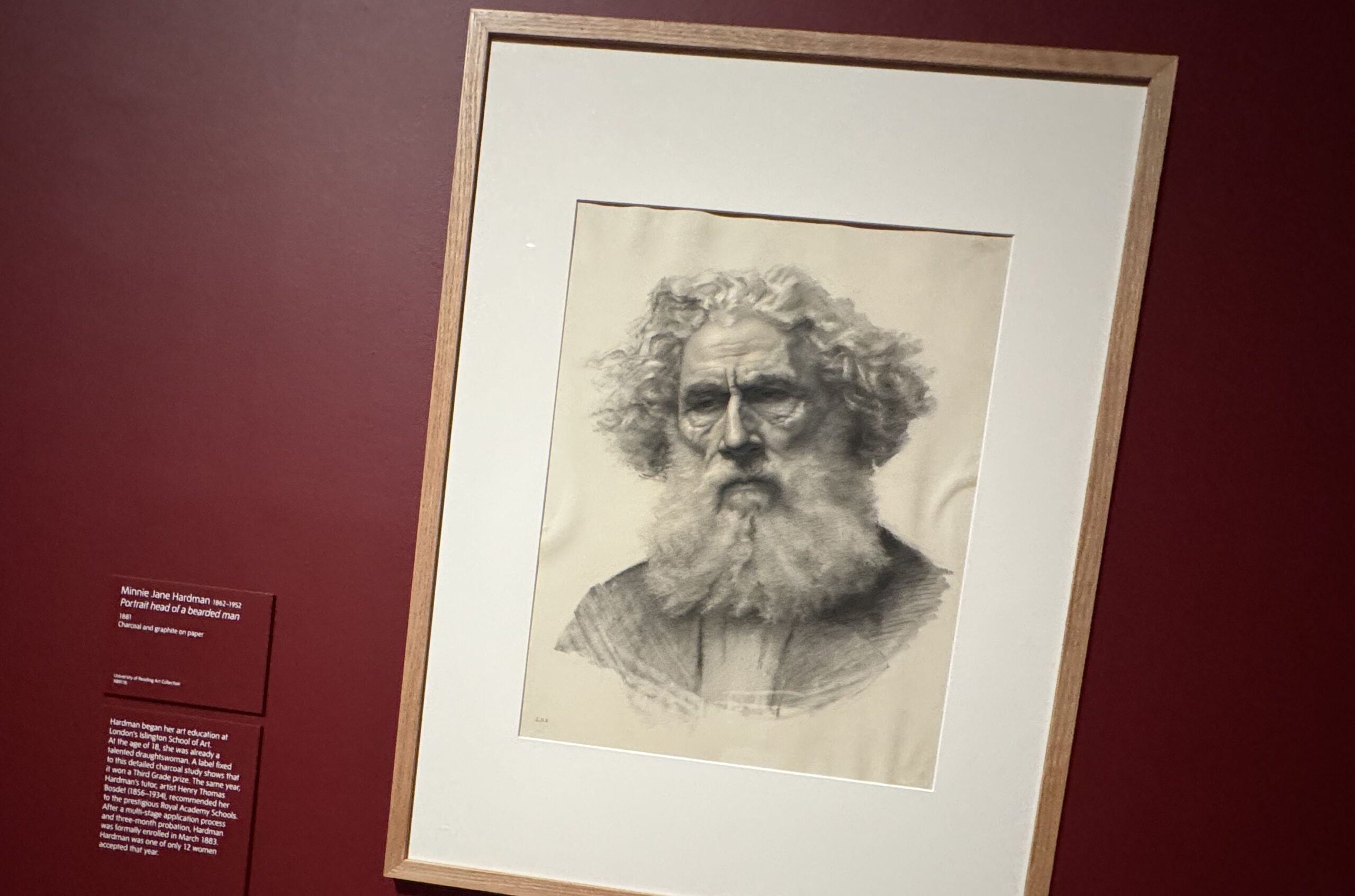

The answer is a simple one: Institutions like the Royal Academy, England’s most prestigious art institution, trained male artists, and promoted men’s work in exhibitions and books, and strategically sought to exclude women. It took the clever Laura Herford who, in 1860, signed her drawings with her initials rather than her full name, to bust through that fraternity.

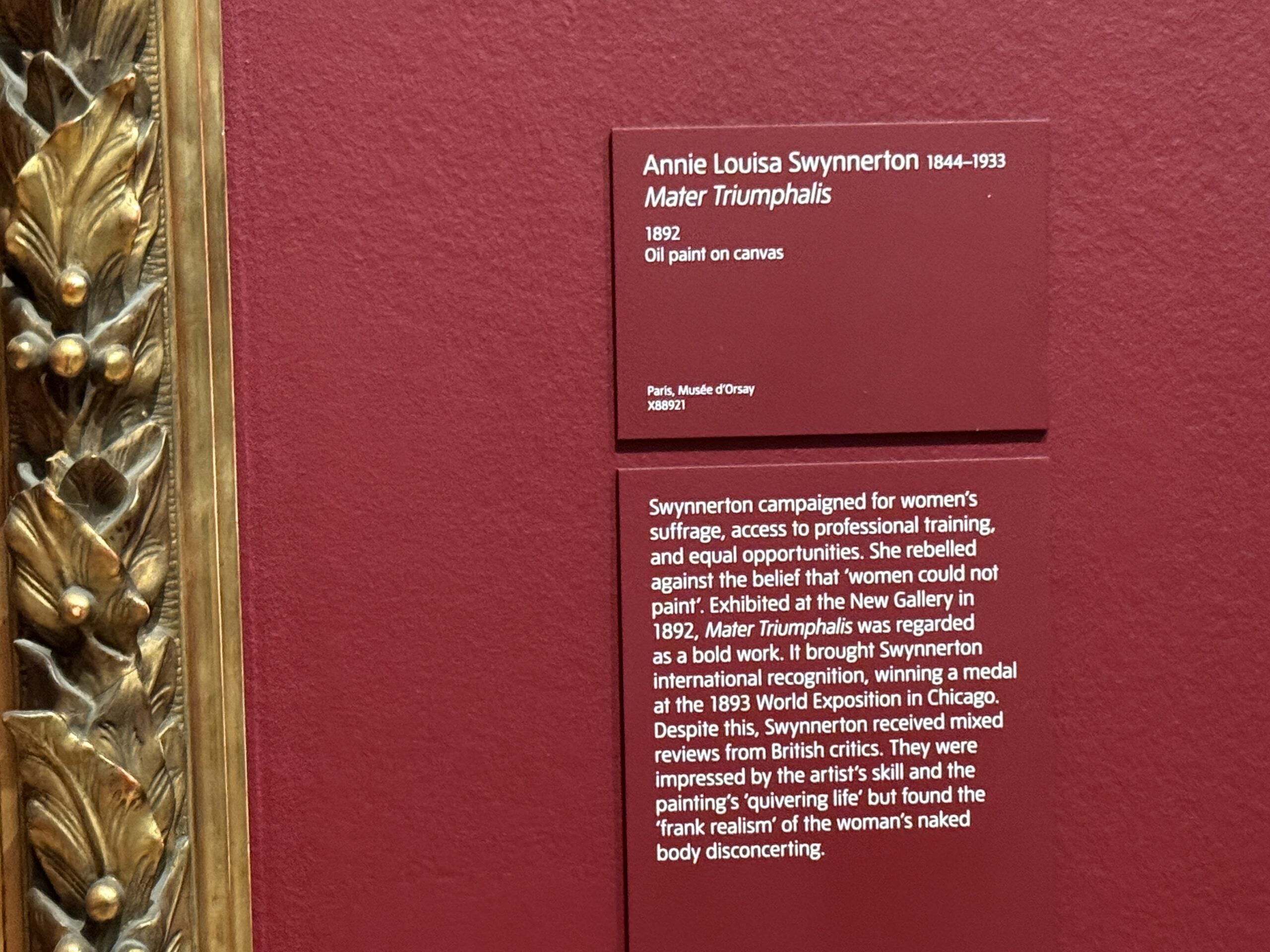

Even then, the Royal Academy saw women as intruders and strictly limited their admission to make sure they never outnumbered male students. The painter Annie Swynnerton, whose work appears in the exhibition, was 75 years old by the time she was finally voted into the academy in 1922. She was invited to join as a “retired associate.”

Laura Knight, also featured in Now You See Us, was the first woman to become a full member in 1936—some 168 years after the Academy’s founding. It was only in 2011 that female professors were allowed to teach at the school. And it wasn’t until 2019, at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, that it got its first woman president, the printmaker Rebecca Salter.

The show also demonstrates how the slow campaign for women’s parity in the art world has been led by—of course!—women scholars. Art historians such as Letizia Treves and Sheila Barker, for example, have led renewed interest in Gentileschi.

There’s a strain of art criticism that rejects the idea of implicating an artist’s biography in appraising a work. But in the case of works created by women under extraordinary circumstances, it seems almost impossible to avoid it.

Too bad the exhibition’s coy title—Now You See Us, like a cheeky game of peek-a-boo—masks its radical potential. If museums and galleries truly wish to contribute to the advancement of women, the challenge is in finding direct and captivating ways to ensure that its underrepresented artists are not just seen, but heard.